Competing ‘State Identities’ & Ethnic Ambiguities

In the absence of a genuine Pakistani state or nation-state identity what are Azad Kashmiris?

It is at this point that we enter the quagmire of the Kashmiri identity dialectic which in the UK some pro-independence actors from Azad Kashmir have been pushing as the ‘Kashmiri National Identity Campaign’. These individuals are extremely sincere and hardworking. They are generous with their time and money, and committed wholeheartedly to any kind of enfranchisement for the nationals of divided Kashmir State that no one really cares about.

They are not, however, imaginative or creative, and neither are they very probing when it comes to deconstructing the conflict and understanding Azad Kashmir’s stake in it. The mainstay of their followers is just tribal whilst many in their ranks are incapable of mobilising their own peers and circles.

They tell us, “Pakistan hates us and exploits us because we’re ‘Kashmiris’”. When they use the term ‘Kashmir’ they use it as the basis of an illusory national space comprised of all the territories of the undivided State pre-partition. In other words, Pakistan is a nation state and Kashmir is also an occupied nation state in the loosest political sense of the term. They are not using the term in any cultural, linguistic or ethnic sense but in a way that is diametrically-opposed to the imposition of the Pakistani and Indian labels.

Are we ethnic Kashmiris (Kashur speakers) by virtue of occupying a national space called Kashmir’? Well, the simple and honest answer is we’re not, and not because we do not come from a region called Kashmir, but because Kashmir has never existed as a nation state. The most we can say is that our forebears were hereditary state-subjects of Jammu & Kashmir State presently administered by India, Pakistan and China. In other words, they can be Kashmiris on account of being nationals of Kashmir State through geo-national ascriptions – the universal norm of naming practises, but not on account of ethnicity, which like the concepts of race and nationalism, is a social construct. There is no such thing as a Kashmiri ethnicity linked with territory, because the territory of Kashmir has historically always been bigger, much bigger than an imagined ethnic space called Kashmir.

In terms of China, the least problematic of the three countries where state subjects are concerned, its stake in the territorial dispute between India and Pakistan is uninhabited. Thus, China does not have to contend with unruly ‘state-subjects’ or independence movements. Its concerns are limited to manning its borders for geostrategic reasons and diplomatic wrangling with India minus the odd border skirmish.

China is thus more predisposed to Pakistan, and maintaining the current stalemate which otherwise would call into question its claims to Jammu & Kashmir territories. The more this conflict goes unresolved the better for China. And so, China’s love for Pakistan (usually in the form of financial and technological aid and diplomatic support in the UN Security Council) and Pakistan’s reciprocating love for China (usually in the form of accepting such lovely gestures) is not based on any fatal attraction but on geo-political priorities that help sustain the status quo to each other’s advantage.

There are implications here that I will be shortly discussing in chapter 7; suffice to say here, the state subject concept is outdated and borne of a colonial age that is being stretched to somehow give Azad Kashmiris a national identity. In its political-cum-legal context, where the term properly belongs and not in the discourses of ethno-identity-politics, it deals with subordinated classes of ‘persons’ and ‘things’ in a hierarchy imposed by a colonial power. In other words, not only are the colony’s ‘permanent residents’ state-subjects but also its cows and produce and bicycles; you should get the point.

Understandably, those who framed the parameters of this legal-cum-juridical system engineered a status qua that helped perpetuate their rule. They would be surprised to learn that the term is being used as the basis of an illusory national identity by the multitude of tribal and Zamindar communities whose lands they had colonised especially in the absence of a shared sense of belonging.

The ‘State’s “Subjects”’; Servitude and illusory “Kashmiri” Nationality

To briefly illustrate this point for those who might require clarification in weaning themselves off its colonial residues, the term ‘subject’ had a legal meaning not just for hereditary ‘state subjects’ of Jammu & Kashmir, i.e., a demarcated territory of the British Crown, but for ‘subjects’ of British India, another demarcated territory.

In legal discourse, ‘territories’ encompass ‘jurisdictions’ and jurisdictions by necessity have a sovereign power and those subjected to it are known as subjects. In the world of colonial politics, sovereigns were without exception Monarchs and usually male.

To be a ‘subject’ in either of the two jurisdictions mentioned above meant you were subjected to power-dynamics not of your choosing. In the British Indian Empire, the paramountcy of British India superseded that of the Princely States; Imperial Britain was the senior partner, the Princely-States were client states.

We are therefore speaking of a legal relationship between two unequal entities with far reaching consequences. The Oxford English dictionary entry for the verb ‘subject’ is quite helpful here; it reads,

“bring (a person or country) under one’s control or jurisdiction typically by using force”

The status of a subject was usually conferred through birth or descent by mere logic of falling within the jurisdiction’s territorial boundaries; the choice of assuming such a status is thus out of your hands. Individuals lacking this territorial status were categorised as ‘aliens’.

Where we parse the concept according to its historical context and usages, we are strictly speaking of legal duties in the sense of an allegiance that is owed to the Sovereign who would reciprocate with a set of responsibilities owed to his subjects. These responsibilities were seldom discharged as absolute rights, but nonetheless involved maintaining the semblance of security, upholding justice, offering jobs, providing education etc., etc.

If one looks at the ‘hereditary state-subject’ pronouncement of Kashmir State’s 1927 ordinance, one can clearly see these considerations at work. The background to the ordinance is also insightful as is the role played by the Kashmiri Pandit community of the Valley to address their own loss of state-sanctioned privilege (in competition with subjects of British India for state-patronised jobs in Kashmir State), but sadly this theme is outside the scope of the present discussion. What I will say is that Kashmiri Pandits, as they are now being identified anachronistically by Hindu Nationalists as the “real” authentic primordial Kashmiris, never once identitied as Kashmiris, but as Brahman Hindus. The Kashmiri identity, at the time, was Muslim and implied Muslims from Kashmir State, and it was also used in this way for occupational caste Kashmiris in Punjab. The Kashmiri identity had no connections with ethnicity, but the geography of a territory that had clear boundaries. This is exactly how lots of ethnic identities wedded to states evolved, and it had nothing to do ethnic narratives that are now being projected into this historically documented past.

Suffice to say now briefly, the state subject rule was formally enacted to appease Hindu Pandits of the Valley in the face of threats to their jobs from subjects of British India, namely Urdu-speaking Bengalis, Beharis and Panjabis. The slogan that consecrated the occasion ran, “Kashmir for the Kashmiris” which literally meant government jobs for the Hindu Pandits because, in their minds, they were the rightful beneficiaries (‘state subjects’) of such legal entitlements.

In practical terms, this meant safeguarding the privileges of a very small minority of Hindu Pandits who were conversant in Urdu, the official language of statecraft. For historical reasons, the official language of the Princely State was Persian and educated Hindu Pandits were traditionally conversant in it. When the Darbar (Royal Court) decided to switch to Urdu in 1889, the Hindu Pandits were instantly disenfranchised as the State’s patrons could now rely on a steady stream of loyal Dogras and Hindu Panjabis from British India. The Pandits were thus forced to learn Urdu, which they did to guarantee themselves ongoing access to state patronage. They demanded this privilege by way of a ‘right’ owed to them as hereditary state subjects of Kashmir, thus the slogan, “Kashmir for the Kashmiris”.

In maintaining this position, they weren’t advocating an inclusive-message of brotherly fraternity and universal rights with Muslims, whether from the Vale or outside.

To the advantage of the Hindu Pandits, everyone else was practically excluded from the enjoyment of this supposed right given the absence of state-run schools in predominately Muslim areas. These state of affairs were the product of deliberate policies that sought to patronise certain groups aligned with the Darbar. The overwhelming majority of Muslims, including those in the Valley of Kashmir were illiterate. Hindu Pandits immeasurably benefited from what appeared to many, to be a Hindu status quo, although the Pandits were distrusted by the Dogra Rajput patrons of the State. The Dogras for their part sought to curtail the influence of the Hindu Pandits by encouraging members of their own ethnic group to take up such jobs even if it meant recruiting them from outside the State. Ethnic Dogras were not only located in the State of Jammu & Kashmir, and neither were Hindu Pandits exclusively located in the Valley of Kashmir, which should help highlight how such identities are construed through times of social and political contestation.

Understandably, subjects of the Princely States were not subjects of British India because they were ‘subjected’ to a different jurisdiction, namely that of a different Sovereign. On account of being born outside the direct jurisdiction of the British Crown, these persons did not owe duties to the Crown and neither were they entitled to reciprocating rights within the State. So what of the responsibilities owed by the Sovereign of a Princely State to his subjects when they were outside his jurisdiction, not forgetting that his power ordinarily wouldn’t extend beyond his borders?

In these circumstances such persons were legally categorised as ‘British Protected Persons’. It was part of the arrangement between the Princely States and the British Indian Empire, that the latter as the dominant power in the subcontinent would be responsible for the external or foreign affairs of the former, its defence and communication. Because of this arrangement state subjects travelling outside their Princely States (for example in French, Dutch or American colonies) were nonetheless afforded formal protection by way of the British Crown. This same protection was afforded to the Indian Princes as well who were also categorised as ‘British Protected Persons”. In this more restricted sense, the Princes and their subjects were subjects of the British Empire.

Whether some states were larger than others and had more control over their internal affairs (and thus semblance of greater ‘sovereignty’), is neither here or there for the basic claim that they were essentially high-level clients. The real masters were those who devised the rules and then subjected everyone else to their jurisdiction.

This is the basic gist of the hereditary ‘state-subject’ category as it historically applied to Kashmir State, the other 564 or so Princely States and British India. Whatever its peculiar specificities given how the idea developed and was consecrated in Kashmir State through the agency of a powerful but privileged minority, the underlying priority remains the same when applied to disparate colonial territories. Fundamentally, the concept has nothing to do with our modern sense of nationality when applied to a nation state in the crucial sense of belonging to a nation and enjoying a reciprocating sense of nationhood symbolically with all the attendant legal and political benefits that come by way of the category.

In the years and decades that accompanied the demise of the British Empire, nationality laws moved in the direction of a new legal category, namely that of the citizen.

In its original usage, the new term distinguished between residents of the British Isles and those of the former colonies who were still categorised as ‘British Subjects’. The rationale behind the new category was to control immigration to Britain from the former colonies who on account of their status as ‘subjects’ of the Crown were legally entitled to come to the mother country without any visas, procure employment and settle in Britain.

As time progressed and the legal discourse evolved, our modern concept of citizenship was born. We no longer speak of ourselves as subjectsmdespite the term’s legacy in legal discourse but rather as citizens, with rights and liberties that are protected by the courts and not merely handed down to us via an unaccountable Monarch or an unimpeachable Ruler.

If we understand the concept correctly, it shouldn’t come as a surprise to then learn that subjects of British India didn’t self-affirm as Britons, or contemporaneously as ‘Britishers’ willingly or otherwise. It would have been a rather curious self-ascription for those demanding independence from Britain, shouting from the tops of their throats that they demand independence because they are the legitimate subjects of the British Crown! It would have been even more curious had these pro-independence subjects argued through some warped dialectic that their status as Crown-subjects automatically made them inherently British especially as they sought to eviscerate British rule.

This is akin to arguing that the state subjects of Jammu & Kashmir State are all ‘Kashmiris’ because the British lumped them all together into a ‘territory’ which British officials lazily and incorrectly called ‘Kashmir’. How can anyone publically affirm an innate sense of belonging to a fabricated territory on the basis of a legal-cum-colonial category that sought to maintain power-dynamics to his disadvantage? If this is not an absurd position then we must find a new definition for the word absurdity.

Moreover, many Hindu nationalist writers given how ethnic primordialism works have observed that ethnic Kashmiris from the Valley poke fun at non-ethnic Kashmiri ‘state subjects‘ pretending to be Kashmiris. Aside from the stupidity of these incredibly ignorant people who have no sense of ironies, when they all claim to be ethnic Indians (linked to the River Indus), or from Bharat (an Indo-Aryan tribe linked with Eastern Punjab), hailing from different ethnic and linguistic identities, we are dealing with poltical propoganda, and not ethnic arguments.

It also may be the case that this representation is being influenced by Hindu-Pandit nativists trying to disconnect Muslims of the Valley from the wider Muslim population of the State, or Pakistan’s ISI intelligence services – greatly despised in Azad Kashmir given how they play communities off other communities (divide and rule). Howsoever we look at this dynamic, the Kashmir label is territorial shorthand for those expressing opposition to Pakistan in solidarity with Muslim Valley Kashmiris fighting against India.

Political propagandists who would like to reduce the Kashmir Conflict to troubles in the Valley alone are intellectually dishonest of the actual conflict between India and Pakistan. The Kashmiris divided between Indian and Pakistani checkpoints are ethnically related to Azad Kashmiris. The propogandists are also unfamiliar at best, or disingenuous at worst, with how the world perceives Kashmir, namely a conflict between India and Pakistan, and not merely an ethnic space located in the Vale of Kashmir, a small area of the much wider State. Ethnic identities do not have historical antecedents, not least because ethnicity is a modern concept like race and nationality. This nonetheless reinforces the claim that the Kashmiri label does not work at the grassroots level in Azad Kashmir, or Pakistani Kashmir (Pakistan and India’s attempt to disconnect Muslim Kashmir from Muslim Jammu); the British Azad Kashmir Diaspora belongs to a myriad of different overlapping identities, landed and occupational. The Pakistani Occupier plays on these ambiguities, unaware of the irony that they have gone within a couple of generations of being called Indians to self-affirming as Pakistanis, all the while they want to lecture Pro-independence Azad Kashmiris about their primordial identity as non-ethnic Kashmiris to somehow deny them the right to self determination within the context of a State called Kashmir. The Kashmir Conflict exposes Pakistan’s hypocracy on Azad Kashmir, and nothing will change the cold facts that I present to my readers here.

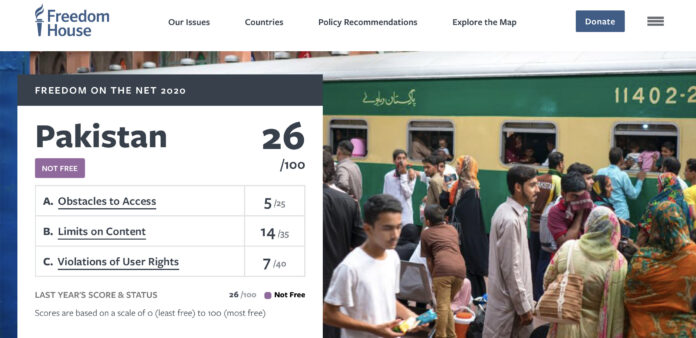

“In June 2018-2019, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released the first-ever report by the United Nations on human rights in Kashmir. The report noted that human rights abuses in Pakistani Kashmir were of a “different caliber or magnitude” to those in Indian Kashmir and included misuse of anti-terrorism laws to target dissent, and restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression and opinion, peaceful assembly, and association”.