People everywhere want to learn something about their past. I did too. I was born in the UK. The first member of my direct family to come here was my maternal grandad. He was a veteran of the British Indian Army. Terms can be misleading, so I should point out that he was from the erstwhile Kashmir State, and not British India.

My grandfather fought for the Allied Powers during WW2, and was involved in the military operations against the state forces of the Princely State, an indigenous uprising against an Autocratic Ruler. This is what my dad tells me.

Maharajah Hari Singh Bahadur was the last Ruler of Kashmir State, and he wanted his State to remain Sovereign and independent of the two countries to be formed out of British India. And so, he signed a standstill agreement with Pakistan, which was of critical importance to the lives of ordinary people. Kashmir’s lifeline to the World went through the mountains of Pakistan westwards to West and Central Asia and southwards to the Plains of North India. One can draw comparisons with how Putin is impeding Ukraine’s wheat from reaching the world today.

India refused to sign a standstill agreement with the Maharajah, but resigned itself to the possibility that Kashmir would eventually join Pakistan because of its Muslim population and geographical contiguity. The logic of partition was easy to understand, Provinces of British India that had Muslim majorities were required to join Pakistan, whilst those with non-Muslim majorities were required to join India. Kashmir neighboured North West Pakistan and more than 75 percent of its nationals comprised Muslims, but it wasn’t a Province of British India.

Kashmir was a Princely State, not part of British India, but a colony of the British Indian Empire; two separate jurisdictions. Oftentimes, the two distinct units of territory get conflated.

Princely States were not subject to Britain’s Partition Plan, (Radcliffe Boundary Commission). The Rulers of Princely States had to decide which of the two countries they wanted to join. Hypothetically speaking, there was a third option for independence which was not explicitly countenanced by the Indian Independence Act, 1947. It was merely implied in the absence of Princely States not acceding to either India or Pakistan (the lapse of power). Much is made of this ambiguous possibility by Indian and Pakistani Nationalists and Kashmir’s Pro-Independence Movements. The final decision of any Princely State would be ratified by the people in a referendum or plebiscite, a democratic component that empowered ordinary people.

Sensing weakness on the part of the Maharajah, Pakistan surreptitiously infiltrated the State, compelling the Maharajah to accede Kashmir to India to save his life and that of his nationals from “marauding forces”. He was airlifted to safety in India and forced by the Indian Government to abdicate his throne. Pensioned off and not allowed to return to his State because of his pro-independence aspirations, he became a footnote in history.

The decolonised Dominion of India had determined that it would become a Socialist Republic based on democratic values for the enfranchisement of all citizens, and not just native clients or elites whom Indian activists had accused of propping up British colonialism for nearly 200 years.

This is an interesting proposition.

To give context to such an indictment, the British Indian Army consisted of 250 thousand soldiers; approximately 210 thousand were natives, whilst the rest comprised of an officer corps made up of Europeans. On the eve of Partition there were 565 Princely States that were not directly ruled by British India. They owed an oath of allegiance to the British Crown, and had private armies to ensure law and order within their regal principalities. British India kept a check on these forces to ensure they never grew in size or power to become a potential threat to the Paramount Power. To appreciate India’s enormous population, some 570 million people were under the physical occupation of an Army that was no more than 250 thousand soldiers. In other words, Indians collaborated against Indians in the perpetuation of a foreign occupation that benefited them, or at least, this is what has been argued by some nationalist writers.

Ordinary Indians were excluded from a status quo that connected native clients with rulers, and lacked political agency to have control over their affairs. British Colonialism was rooted in economic exploitation that marginalised people through autocratic policies. It had been no different to older systems of exploitation that included the Roman and Byzantine Empires, various Muslim Powers and the Hindu Caste System. The lower classes of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds seldom mattered, whilst native clients furthering the interests of Overlords were suitably rewarded and empowered.

This is what is meant by the phrase native clients.

Approximately 3 months after partition, an uprising occurred in Kashmir State in what became Azad Kashmir by disgruntled and disbanded soldiers unhappy with how they were being treated by the Maharajah. He was a Hindu Ruler, whilst they were Muslims, but neither interest framed its cause in religious terms. The rebellion was aided by tribal incursions from what was then the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) from the Hazarah country of today’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. It was covertly directed by the Pakistan Army, which was still under the control of British Officers. The Afridi Tribals, as they were described by Pakistani and Indian writers disparagingly at the time, once in Kashmir Territory committed crimes against the people, raping women, murdering men, stealing property and abducting females. The victims were not just Hindus and Sikhs, but Christians and Muslims.

Partition 70 years on: When tribal warriors invaded Kashmir

Some two dozen shops sit quietly on both sides of a security barrier that marks the border between Kashmir and the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. There is nothing to suggest that hordes of militant Pathan tribal warriors who invaded Kashmir exactly 70 years ago to start one of the world’s most enduring territorial conflicts actually broke into the region through this very point.

There’s no nice way of stating facts for what they are, but by the standards of any moral or political code, Pakistan’s invasion of Kashmir was an act of brazen treachery given it had signed voluntarily a standstill agreement with the Maharajah to maintain normal relations. It smacked of the same duplicity that America accused Pakistan of just after 9/11, when its Military hid Osama Bin Laden. Pakistan was tasked with finding Bin Laden, receiving billions of dollars of Military Aid to be part of America’s War on Terror. This funding dated back to the Cold War when Pakistan had chosen, again, voluntarily to join the West (America) in its fight against the Soviet Union. Indian and Pakistani scholars speak of the ensuing and unruly alliances as the Great Game, overshadowing an older British colonial entente to contain the rise of Tsarist Russia (1721 – 1917), and then the USSR, post 1917. A lot of the aid procured from Saudi Arabia and the West during the Cold War, intended for the Afghan Resistence disappeared into unofficial channels of the Pakistan Army.

India eventually intervened and managed to repel the tribals back into Pakistan. Kashmir State was bifurcated between the two countries. Years later, Pakistan sold and gifted areas of Kashmir to China. India fought a number of border wars with China to retain those lands.

Kashmir is trifurcated between three countries, India, Pakistan and China.

Afterwards, Pakistan began to propagate the idea that the Kashmir Uprising was a Muslim Rebellion against a Rajput Hindu Ruler, which it wasn’t. It was an indigenous anti-taxation movement spurred by grievances of Muslims and non-Muslims that predated the creation of Kashmir State in 1846, similar to how America’s Settler Movement rebelled against the British Crown in its own War of Independence, 1775 – 1783 CE. Kashmir and its neighbouring Hill Tracts have been under foreign occupation since the 1500s. It didn’t matter if those being squeezed were Muslims or non-Muslims. The one thing that united the people against the rulers and their native clients was the fact that they were being exploited, whilst those extracting resources from them lived elsewhere.

“No taxation without representation”, Patrick Henry, 1765

When British India was finally partitioned on the 15th of August 1947 between India and Pakistan, Muslim soldiers in what became Pakistan elected to join the Pakistan Army, which is what my maternal grandad did and his peers. These guys were not nationalists of Pakistan per se, and to argue otherwise is to distort history and misappropriate their memories for the purposes of political propaganda.

The Muslim Soldiers of European Empires – the Paradox of Colonialism

Of the 1.5 million Indian soldiers who fought for Britain during World War I, approximately 400 thousand comprised Muslims. In fact, when one does a tally of Muslims involved in the war, soldiers and labourers from 19 countries – ex-colonies today, 2.5 million Muslims were actively engaged in wartime duties. According to other sources, it was around 4 million Muslims. It is quite interesting that critiques of colonialism from the perspective of colonised “memories” – always projected backwards, ignore how large numbers of the colonised made colonialism possible in the first place, which just shows how history is a lot more nuanced than the ideological reimaginings of nationalists.

In fact, the way British colonialism is being instrumentalised to tell a particularly skewed leftwing story fails to capture the collaborative nature of the enterprise in question. It also fails to capture the struggles, sacrifices and efforts of ordinary Britons opposed to colonialism. Some of the staunchest critics of the colonial project included native Britons, who were a constant thorn in the side of the Rulers. For instance, reformist Christians that included the Quaker Movement were the first to agitate against the North Atlantic Slave Trade. It would be very hard to place such Protestants on the left of politics.

Moreover, 800 thousand Britons lived in India at the time, three and four generations removed from the first settlers. It is not unreasonable to proffer the view that they were not all susceptible to the “perks” of Occupation. Many followed their convictions and spoke truth to power at a time when Indian elites were colloborating with the Power Structure to oppress ordinary people. This version of British Colonialism is an inconvenient alternative to the populist narrative being churned out. George Orwell would fall within the camp of Britons who fought tirelessly to eradicate the scourge of man’s inhumanity to fellow man.

The forgotten Muslim heroes who fought for Britain in the trenches

A biting wind whips across the rolling countryside, cutting through the crowd gathered on a hillside overlooking Notre Dame de Lorette, France’s national war cemetery. Huddled amid what remains of the 440 miles of trenches that made up the western front, they shudder out of shock and surprise rather than cold while listening about life for the men who endured the horrors of the first world war.

My maternal grandmother passed away in Azad Kashmir – the area that was supposedly liberated by Pakistan. My maternal grandfather remarried. After the war, he migrated to the UK where he passed away in 1984 under a visa scheme that allowed soldiers of World Wars I and II to resettle in Britain. I was a young child at the time and I accompanied his body to be buried in his ancestral graveyard. My father had uncles and cousins who fought in World Wars I and II. They weren’t all conscripted into the regiments. Some of them volunteered to fight for Britain.

The British Indian Army was an important recruiter in the area. Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus did not have the anxieties anti-colonial activists embody today, thrashing the evils of European Colonialism, hating ‘old money’, ‘class power’ and that most overstated of demons “white privilege” – I entreat my readers to speak to ordinary white Britons to appreciate how false narratives emerge around illusory identities. Because of how certain segments of the wider population were classified by colonial ethnographers through what was, in effect, a pseudo race science, entry into the Army was permitted for “martial races” and those from landed (agricultural) backgrounds. The same policy was applied across the colonies and even Scotland’s Highlanders were classified as a martial race, who fought in Britain’s wars.

My paternal grandad died in Baluchistan working on the railways as a telegraph operator. He was among a small group of people who could read and write. He died in his 20s orphaning his only surviving child, and leaving behind a young widow, who would never remarry again for 70 years. She lived well into her 90s and described vividly what I would describe as a prolonged period of downward mobility, only to be rescued dramatically by members of her family leaving the State. She was a rich source for the transmission of oral history and a lot of what she narrated, despite having no access to literature, was corroborated by the historical record. She passed away in the UK where she’s buried.

My grandparents’ generation were an industrious lot, they left their homes in search of work and travelled thousands of miles. They had an indomitable spirit to deal with whatever life threw at them.

A lot of them never returned home.

Decades earlier, I’m told of relatives who worked on the British merchant ships docked in Bombay, this was the norm back then. Most of the people from Kashmir State, or the areas around the old market towns linked to trade and soldiering sought greener pastures elsewhere. What became Pakistan Occupied Kashmir; I’m trying to use the correct terms for Azad Kashmir irrespective of how it offends Pakistanis, was peripheral to centres of power, although this is not to say that it wasn’t integrated within the wider structures of Empire. But, as I will explain in due course, the selective use of the Mirpuri label for a much larger Azad Kashmir population wrongly restricted to a District has political priorities. It had never been used as an ethnic or regional identity for native segments of Jammu & Kashmir, which is how it is being deliberately instrumentalised today, negatively.

Some adventurous expatriates of Jammu & Kashmir State on their various journeys across the world courtesy of the merchant navy, jumped ship and ended up in the New World. One of my dad’s cousins settled in America years before any of them came to the UK. Others ended up in Australia, Hong Kong and even East Africa, where they settled down and took local wives. This is earlier than the 1950s and predates the repetitive history that is being celebrated on BBC platforms by Asian commentators extolling the commonwealth immigration story of the 1960s that closely approximates to their past.

See below how contrasting stories of Monga Khan, Jammu & Kashmir are told by different interest groups to appreciate the spread of false narratives.

AUSSIE Posters – Peter Drew Arts

JANUARY 28, 2016 I am traveling Australia sticking up 1000 poster of Monga Khan, the Aussie folk hero…. The photograph of Monga Khan was taken 100 years ago in Australia. He was one of thousands of people who applied for exemptions to the White Australia Policy.

There is a purported authenticity of identity to such stories that seems to trump the authenticity of the actual stories being told to western audiences, selectively. Azad Kashmiris are missing from the stories despite being the pioneers of South Asian immigration to the West. What is curious is how they are constantly disconnected from Kashmir, oddly forced onto the margins of a Punjabi identity that never existed in history. They are then problematised as being the sole vehicle for radicalisation, honour crimes and oddly, grooming gangs in the UK, which is a good indication of how subtle bias works when it becomes a full blown narrative.

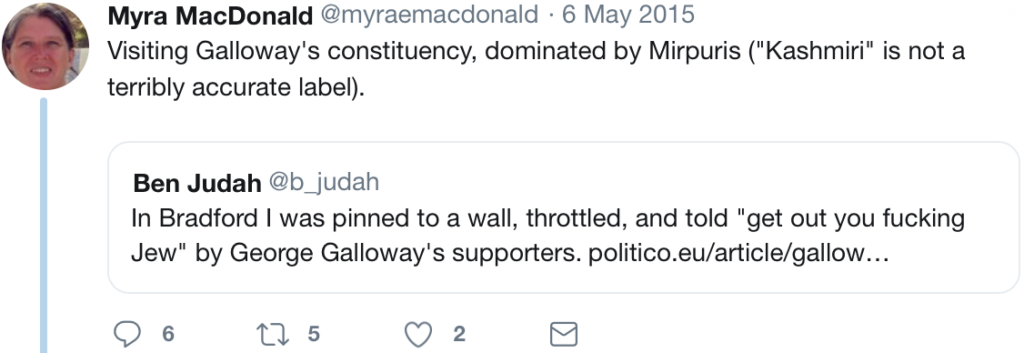

See the following quote in Madeline Bunting’s grossly inaccurate portrayal of Azad Kashmiris after the 7/7 suicide bombings.

“Within Pakistan, Mirpur is to the dominant Punjabis what the Irish have historically been to the British.”

Revealingly, when it transpires that the journalists and reporters had misunderstood the identities they were offering insights on courtesy of a journalism that needed to get the story out quickly, there have been no apologies, or corrections. For instance, The 7/7 bombers did not originate from Azad Kashmir, making the use of the Mirpuri ascription incorrect. In fact, they originated from the Punjab Province of Pakistan, rendering them Muslim Punjabis, and yet we had an entire narrative weaved around the mistaken identity of suicide bombers courtesy of Pakistani informants misleading the British Public.

Madeleine Bunting: Mirpur history may explain suicide bombers

The room is packed, the discussions go on way beyond the allotted time: this was a meeting of young professional Muslims in London at the weekend. The anguish and self-criticism was unstoppable as they struggled to find answers to how their faith could have nurtured such a perversion as suicide bombers in London.

Who gets to narrate history?

So, there you have it. We can get snippets of history from the personal stories of forebears, narrated to elicit a deep connection with the past even when imagined, which should not be conflated with invented. Benedict Anderson’s pioneering ‘imagined communities’ is an excellent introduction to how nationalistic identities have emerged and the myths associated with the supposed origin of countries. There is always an imaginative component to how we narrate past events.

Nationalism is a story that morphs with other stories, and the upwardly-mobile tend to approximate to the stories of the powerful. There is a reason why nationalism appeals to a particular audience, what sociologists call the “dominant group”. It is representatives of dominant groups who get to memorialise their stories for everyone else, and not the dispossessed, whose stories linger in oral tradition. If the dispossessed challenge the dominant status quo, their stories are usually ignored, mocked, problematised and erased – and in that order too. In the age of Digital Media this is becoming a massive problem and a huge liability for genuinely open societies that value the free flow of information and ideas. This has serious implications for Azad Kashmiris in the UK who want to understand their past as honestly as possible outside India and Pakistan’s incessant obsession to own Kashmir and her memories.

Still, none of this told me anything about the distant past. I wanted to learn something substantive about the history of Azad Kashmir, without getting bogged down by the politicisation of historical events. I wanted to learn the origin of its culture through cross-cultural references. How was the region configured within the documented history of older territorial configurations? Where did the native language come from? Who exactly were the distant forbears of modern-day Azad Kashmiris; where did they come from? Within the wider discussions of Indology and Indo-European Studies, did they originate from Central Asia – nomadic steppes; or West Asia – neolithic plains, through purported migrations that date back to the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)? We are told Neolithic Iranian Farmers merged with Central Asian Steppe Nomads, forming a hybridised population that eventually migrated into the Iranian Plateau and North India. Currently, human genome studies (genetics) are pioneering the way forward with impressive findings – lots of Azad Kashmiris descend from populations related to West Eurasians that include Europeans. The spread of a light skin allele named SLC24AF into the subcontinent evidencing shared descent is a point in question.

Watch The Journey of My Maternal Line From FamilyTreeDNA

Discover your DNA story and unlock the secrets of your ancestry and genealogy with our DNA kits for ancestry and the world’s most comprehensive DNA database.

This is a fascinating history of shared descent across thousands of miles.

It was said of the BMAC population that they were the first to use the word ‘Arya’, but the related word ‘Aryan’ carries racist connotations courtesy of German Nazi misappropriation. When one looks at how the word Arya was actually used by its original progenitors, it implied nobility, and not race, language, or ethnicity. The Achaemenid Emperors, Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great, 5th century BCE, were born into this heritage, as were the Rulers in North West India, who would go on to create Tribal Confederacies called the Aryavarta, or the Aryan Realms. There was a gradual movement of Indo-Aryan speaking tribes from the north west into the North of India and then beyond into the forested areas of the Deccan Plateau, moving to the extreme south into Sri Lanka. Populations fused and coalesced with other populations giving birth to ancient Iranians and ancient Indians, and other nationalities.

Iran means ‘the land of the Aryans’ but its application to Persia is recent. Arthur Comte de Gobineau, a French Aristocrat visited Persia in the 1850s and was fascinated by its “Aryan” history. He helped popularise the idea that Persia’s ancient Rulers like India’s ancient Rulers were originally of Aryan stock. Subsequent populations were greatly “mongrelised” unlike the Germans and himself! Gobineau believed that the Nordic Race represented the truest specimen of Aryan descent-claims. Subsequently in 1935, the Shah of Persia changed his country’s name to Iran, an ascription that had historical precedent before the advent of Islam into the region. I began to realise how ancient history with a documented legacy in archaeological sites, numismatics and ancient manuscripts could be retold through political priorities that were being moulded to fit an idealised version of past events. I found this to be deeply disturbing.

History of the Swastika

The word swastika comes from the Sanskrit svastika , which means “good fortune” or “well-being.” The motif (a hooked cross) appears to have first been used in Eurasia, as early as 7000 years ago, perhaps representing the movement of the sun through the sky.

The Homeland Question

Was South Asia the original homeland of the Indo-European dispersals? Intially postulated by colonial writers, it has been an argument put forward by Indian scholars with little acceptance from their European counterparts, who seem captivated by an Indo-European past that puts Europeans at the centre of the story. Naturally, people will prioritise aspects of a shared history that applies to them the most. This is perfectly understandable. However, West-Central Asians and South Asians, (two deeply misleading geographical constructs), have become incidental to the Indo-European shared story according to Indian researchers, despite being the source of the actual memories. Vedic texts, the Avesta and archaeological inscriptions all point in that direction.

“I am Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries possessing all kinds of people, king of this great earth far and wide, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid, a Persian, the son of a Persian, an Aryan, of Aryan lineage.” Naqsh-e-Rustam inscription, dated 521 – 486 BCE.

The great Prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra) was also identified as an Aryan in the historical record. Scholars have revised the date of his birth to 1500 years before Christ to appreciate the older linkages. Some historians have argued that Zoroastrian mythology and ritual practises heavily influenced the Old Testament. But even this fascinating enquiry becomes redacted when online commentators take ownership of the various writings committed to extolling the conjectural nature of the past. I began to discover that the facts that I had been learning through scholarly books and peer reviewed journals were different to the simulated facts popping up on various websites purportedly exploring the same terrain. The online dilettante were reducing decades of contested scholarship to chromosomal haplogroup myths, maternal and paternal, in ways that would seem unintelligible to the population geneticists researching the older migrations, the material cultures created in their wake and the associated literary traditions. Even the hypothetical maps of the journeys taken by various haplogroups, populating different regions, are distorted to fit the priorities of the people producing the online narratives.

But still, these were the sorts of questions that intrigued me.

I wanted to learn actual facts about the regions that intersperse Azad Kashmir from the disciplines of archaeology, cultural anthropology and historical accounts from different literary traditions. Sanskrit and Pali Prakrit texts are of vital importance, which include the Hindu and Buddhist canons. Ancient Greek and Latin writings about India are similarly important. Even classical Arabic travelogues dating to the period when Muslim Arabs entered “al-Hind” (India) from the direction of Baluchistan can shed enormous light on how Azad Kashmir was never considered part of al hind wal sindh but Kashmir, which at the time was ruled by the Karkota Dynasty, 624 BCE – 855 CE. The Karkota Rulers pushed the boundaries of their Kingdom deep into the North Indian Plains, but after their demise Kashmir returned to being a peripheral power vying with neighbouring Hill Tracts. Persian speaking Turks came later through the direction of the Khyber Pass post 1000 CE, but even their Turkic predecessors (Turushka) were mentioned in ancient Indian Texts. They converted to Sufism, which was influenced by Buddhism, which grew out of the soil of India. It was a very different affair to the Juristic Islam that is being primordialised across Muslim minority communities in the West.

I was curious to learn what population geneticists had to say, and their controversial finding that there may have been truth to the endogamous caste system that lasted 2000 years after it was introduced into India, something deeply troubling for scholars operating within the social sciences, and for good reasons too. The evils of the Nazi Regime and its plan to breed into existence a pure “Aryan” race, breeding out racially faulty “whites” – white people of the lower social classes were the actual targets. The Nazis wanted to exterminate Jews, Gypsies and even the Slavic Race in places like Ukraine. The disabled and those with mental health issues were euthanised. Perturbed by man’s inhumanity to man, I thought where exactly is this ‘white privilege’ in the inner-cities of the UK?

The wholesale murder of “inferior peoples” by Nazis has seldom left the conscience of Western Academia. 6 million dubiously dubbed “Semitic”, i.e., “Middle Eastern” Jews were exterminated on the basis that they were not genuinely white and European (Nordic), which is an interesting proposition given that the historical Jesus of Nazareth, and one third of the Christian Godhead, was of Jewish descent with roots in the Middle East. In western literature, contradictions like this make for great ironies – a recurring device in Greek Tragedy.

Astonishingly, the Latin and Greek history of the European Continent was also demoted to being of lesser value than the achievements of the Nordic Race, considered racially superior to the Mediterranean and Alpine Races of Southern and Eastern Europe. Interestingly, German speakers lacked a national homeland when race ideas were first emerging in Europe during the 1800s, having been divided into German Principalities. The German Empire was quite late to join the scramble of oversees colonies in Africa to understand the actual anxieties behind the posturing.

Today, race and ethnicity are giving way to newer narratives based on genome-wide studies. Online commentators projecting through the new identities distort the actual findings of scholars writing about the journey of various haplogroups, spewing disinformation that pops up all over the place, discrediting the efforts of the geneticists. When one visits Indian and Pakistani websites committed to extolling the racial and primordialist history of their respective countries, one encounters enormous distortions and fabrications of actual scientific papers. One can add neo-Nazi websites like Stormfront. One confronts anxieties and insecurities of people who seem to hate the global order because they feel excluded from it, speaking of pure and impure races.

The ethnonationalists of Hindutva India and Islamist Pakistan, not to be conflated with ordinary Indians and Pakistanis – good decent people in my mind like ordinary Europeans – are fighting over 85000 square miles of Kashmir State territory, which doesn’t belong to them. They have created an insufferable environment, so toxic that they’ve become intruders into each other’s conversations. This would be akin to Putin arguing that Ukraine is not really a country of its own, it has always been Russia, a patently false idea.

I wanted to steer clear of visceral hatred, and so I avoided the use of the term ‘Kashmir’. I even dropped using the term Azad Kashmir for Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, self-censoring naively. Both words are an invitation for Pakistani-Indian nationalists, I would remonstrate with myself. I began to use the word ‘Pahari’, an innocuous low-status word for mountain regions and peoples – something I deeply regret now. Pahari simply means from the mountains and can be used for an array of unrelated ethnic groups. It gets conflated with the prejudice and bias of Plains People from North India and Pakistan, upwardly-mobile “citified” people usually of very humble backgrounds approximating to the power structures of their respective societies. There is an enormous body of knowledge that shows how class prejudice can emerge in any society, and from which direction it comes. Indian scholars have written extensively about social prejudice in the subcontinent and how it is interconnected with the caste system. I had my eyes on the Western Himalaya – the north westerly lands, and the mountain passes through which the ancient Nomads entered India – lands eastwards of the River Indus, which is the Persian-Greek word for India.

And so, what did I do?

I typed Mirpur into the Google search engine. I thought I was being smart. Like most British Azad Kashmiris, my grandparents originated from areas north of what is today the dissected District of Mirpur.

I wanted to start my journey into the past from this innocuous and inoffensive location.

It was at this critical juncture that I discovered by accident that Azad Kashmiris were being problematised because of occupation politics connected to the Kashmir Conflict. The hatred in question was deliberate and organised, intended to demoralise British Azad Kashmiris to never lay claim to an identity that was inherently theirs, to stop them from mobilising on behalf of the Pro-Independence Kashmiris.

A word or two about Mirpur; actual documented history

Mirpur used to be a sub-district of Bhimbar which included Rajouri before its reconfiguration during the 1900s. The idea of Mirpur postdates the area’s actual documented history, and it emerges within the ecology of Bhimbar. In the olden days, the region between the Rivers Jhelum and Chenab mapped onto another region called Chibhal, or Jibhal according to how Mughal writers transcribed the word. It was the Mughals around the end of the 1500s who began the process of reconfiguring the mountainous territories they conquered through the help of native clients incorporated into their patronage network.

Historians call this system of feudatory relations the Jagirdari System.

A Jagir is a fief or landed estate. A Jagirdar is a fief holder, usually borne to a kinship lineage, connected to a particular fictive ancestral group of varying status, deploying an array of nobility titles that have become meaningless today given how they’ve been adopted by upwardly-mobile groups claiming connections with the old heritage. The old titles have become popular names disconnected from the past I wanted to research.

In centuries preceding the emergence of the Turkic Muslims Rulers, Chibhal mapped almost entirely onto another ancient region called Darvabhisara, or the Abisara of Greek writers, which was incorporated within a wider region that included Gandhara and Kamboja. Ancient Indian writers postulated that the inhabitants of Darvabhisara were of Khasas descent, explicitly subsuming them within the larger confederation of the Aryavarta – the Aryan Realms.

Kashmir like the neighbouring region of Urasa (modern day Hazarah) was a less influential region within a larger political-cum-tribal centre of power, but its ruling families were connected to the larger regions. The Kashmir of ancient history had always been a peripheral region, but the history of the more powerful regions became ensconced into its own retelling of a shared and imagined history from the vantage of the 12th century CE, when a court official named Kalhana wrote a chronicle of Kashmir’s Kings that stretched back thousands of years. The Rajatarangini, (literally, ‘the River of Kings’) was expanded on by subsequent writers that included Jonaraja. Crucially, it was written in Sanskrit to appreciate which literary tradition was being used in the amalgamation and rewriting of ancient stories and legends. It was then expanded on by Persian writers. This “history” in the loosest possible sense of the term was then incorporated within Mughal writings, having been translated from the Sanskrit into Persian; see Akbarnama of Abu’l Fazl. A lot of Azad Kashmir’s ancient history can be extracted from Persian and Sanskrit texts, without even making recourse to later Urdu-Hindi writings that force Kashmir into an Indian-Pakistani space.

The Mughals would call the Jagirdar System the Zamindar System. The Zamindar were landowners connected to a system of patronage and nobility. The Jagirdari System predates the Mughals by centuries though. Mirpur, and by that term, I do not mean the disinvested and shrunk District of the same name, but the entirety of Azad Kashmir had never been part of the Dominion of India, or the Dominion Pakistan, that emerged out of the Hindustan that was conterminous with the North Indian Plains. The Punjab Plains are, geologically speaking, contiguous to the North Indian Plains, what is otherwise known as the Indo-Gangetic region. Azad Kashmir including Mirpur are not contiguous to the Plains of North India, but the hills and mountains that move westwards and northwards.

Pakistanis are essentially Indians all but in name – there are an equal amount of Muslims in India as there are in Pakistan. In fact, when Bangladesh’s Muslim population is added to India’s Muslim population, there are more Muslims outside Pakistan in the old British India colony than in the country created for Muslims by the British. Interestingly, the concept of Hindustan is actually a Muslim concept, which Pakistani ethnonationalists have volleyed into the lap of Indian ethnonationalists to discredit the idea of ancient India. Of course, there is a Civilisation called India far more older and noteworthy than the political constructs of Indian nationalists who want to politicise that history, whilst Pakistani nationalists want to reject it. Neither of the two groups want to celebrate that past, although both nationalists share a contemporary culture that is almost identical when they resort to Hindi-Urdu, a lingua franca created by the very colonialists they despise.

These ironies are poetic.

At its largest breadth, the expansive District, or Zillah Mirpur, included Mirpur, Kotli, Bhimbar and Rajouri (Tehsil or sub-districts). The second largest valley within Kashmir State – a geographical and geological space, and which constituted an important population centre for the recruitment of soldiers was the Andarhal Valley – (literally, ‘the area between the hills’), and it was located within Mirpur District. Andarhal gets wrongly confused with Mirpur, a small market town and a tribal settlement that dates back to the middle of the 17th century. The historical region of Chamakh, now underneath the waters of the Mangla Dam was the location of the older market towns linked with the Andarhal Valley.

Expansive Mirpur had always been a geo-administrative unit of territory, and not the locus of cultural history best explained through cultural ecology, which in the case of Andarhal spreads deep into mountain country. The inhabitants of Andarhal are mountain people and not plains people, they have been shaped by the cultural ecology of their terrain. When one looks at migrations into the area and the flow of cultural norms, expansive Mirpur is a recipient of cultures coming from the north and west, spreading across valleys until they reach the plains of North India – Punjab and Hindustan. This history is being denied to the natives, who are being encouraged to think of their past through false political paradigms that connect their lands with either India, or Pakistan, but never a centre of gravity located in the mountains beyond India-Pakistan.

When one reads Indian-Pakistani ethnonationalist accounts of Mirpur’s history, it is as if the culture has come from the direction of the Punjab, and this primarily because of politics. It thus goes without saying, geographically and geologically, the entire area of Mirpur District is located within the undulating Hills-Mountains of the Western Himalaya, a mountainous region with a separate history to the North Indian Plains. Native cultures are shaped by their physical ecologies, and one can see this in the words used to describe an environment and the foods eaten courtesy of a region’s fauna and flora.

But, even these innocuous facts of anthropology seemed to be contested by the ethnonationalists, who wanted to relocate Mirpur in the Pakistan Punjab at all costs. Of course, there is a Dam in Mirpur which produces 1500 megawatts of electricity, 3 times more electricity than what the entire state of Azad Kashmir needs, but seldom gets. The Mangla Dam irrigates Pakistan’s Punjab Plains, this water is the national asset of Jammu & Kashmir. It became operational in 1967 funded by the World Bank and Western donor countries – Pakistan lacked the requisite funds to pay for the construction of the Dam. Moreover, it resulted in the dislocation of 110 thousand natives who were poorly compensated and forced off their ancestral lands, forcibly resettled in the most unproductive of aggricultural lands in places like Multan.

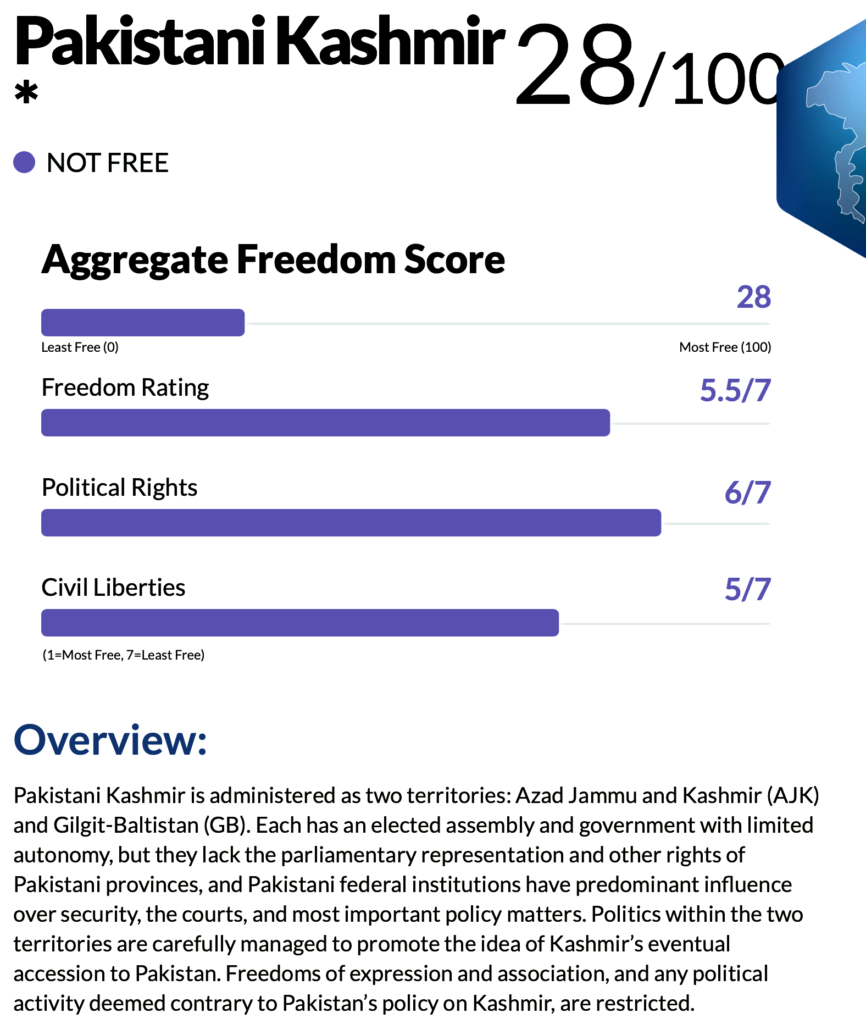

Decades later, tens of thousands of people were again dislocated from their lands to make way for the expansion of the Dam. Pakistan has always suffered from a scarcity of water and electricity. Divided Jammu & Kashmir is a water-rich region and has enormous potential for the creation of Dams. Mirpur Dam’s royalties promised to the native clients of Azad Kashmir, but seldom payed to the supposedly autonomous representatives of the Occupied Territory are many times more than the meager budget sourced from Islamabad.

The Pakistani hand takes more than it gives. It cannot offer Azad Kashmir prosperity or even social stability, because it has nothing of value to give, except internal conflict and inequality. It is an established economic fact that Azad Kashmiris do not need the reapportioning and siphoning of their natural resources by Pakistan – a country that has been exploiting not Just Azad Kashmir’s natural resources but Baluchistan’s too. Entire areas of the Occupied Regions have been deforested of timber, causing arid conditions, hotter temperatures and climate change. Azad Kashmir can fend for itself so long as it has a trading corridor with India, which is the only reason why Pakistan has stopped Azad Kashmiris maintaining and sustaining relationships with the actual natives of Jammu & Kashmir – Britain can become an excellent place to repair the old relationships. Pakistanis are forcing Azad Kashmiris to rely on Pakistani goodwill, when an alternative market exists across the imposed LOC in India that does not need Pakistani middle-men.

In fact, remittences from the British Azad Kashmir diaspora since the 1960s have kept the economy of Northern Pakistan affloat, aside from being a source of British Pounds needed to meet Pakistan’s Balance of Payments paid in US Dollars. The Pakistan Rupee has consistently been losing its exchange value as it is tied to an economy that will eventually falter in light of Pakistan’s demographic time-bomb and levels of corruption and inequality that are off the chart. Ecological disasters are increasing at levels that are unsustainable. Every year, Pakistanis have less money to buy goods from foreign markets, and there is seething resentment in the country between various ethnic and social groups. There is profound hatred for ethnic Punjabis, even the word Punjabi is being instrumentalised as an “insult”, which might account for why some Pakistanis love calling Azad Kashmiris “Punjabis”.

This is not brotherly love, but a smear campaign based on visceral emotions.

I began to realise that Indian and Pakistani nationalists wanted to erase Azad Kashmiris from their distinct and specific cultural ecology because of deeply ingrained insecurities and anxieties about possible territorial solutions that do not include them (Occupiers) in the greater scheme of native representation.

Kashmir State

Kashmir as my readers should now understand is a third country for all practical purposes. It is being fought over by India and Pakistan, whose respective administrations in Islamabad and New Delhi have caused chaos in the wider region. Its fate is similar to that of Eastern Turkistan, where the Turkic Uighur have become a persecuted ethnic minority. Turks of Uighur descent are being erased from their homeland by the Chinese Communist Party – self-affirming Atheists, with the tacit support of interests like Pakistan – self-affirming Muslims, who otherwise like to embroil themselves in the affairs of Occupied Muslims in Palestine. The three interests above occupy parts of Kashmir through military force, and not because of the natural aspirations of the natives, which is a legal right under international law to which both Pakistan and India are disingenuous signatories.

I ask my readers to spare a thought for the Turkic Uighur and what is happening to them and the Muslim World’s complete disregard for Muslim cultural genocide. The Christian West, Jewish Isreal and Hindu India – all three are secular entities, have raised concerns about Communist China’s mistreatment of the Turkic Uighurs, whom include Muslims, Buddhists, Christians and other demographies. The entire Muslim World has abandoned them including Erdogan’s Islamist Turkey because of China’s emerging role in the International Order. In the same way, Russia spreads disinformation about Ukraine and China spreads disinformation about Eastern Turkistan, questions about Kashmir’s territoriality are deliberately collapsed into nonsensical debates about sub-regions, ethnicities, religions and oddly, caste backgrounds to deliberately undermine consensus through divisive and irrelevant talking points.

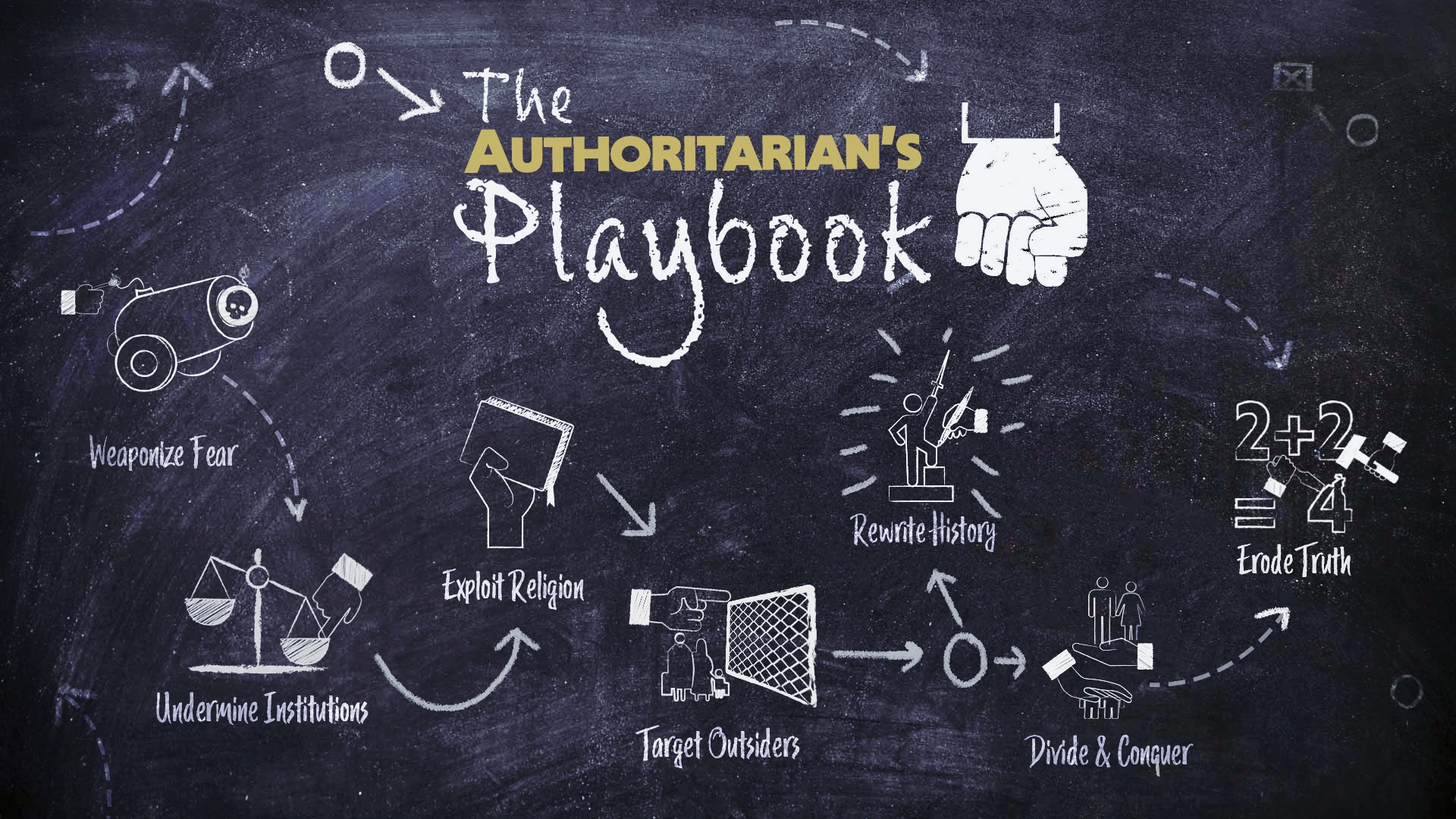

This tactic is taken wholesale from the Authoritarian Rulebook, which promotes a singular identity for itself whilst problematising the plural identities of those it occupies; the Romans had a term for this stratagem, “divide et impera” (divide and rule). Colonial administrators understood the perils of ‘dividing and ruling’ improperly in the way I’ve tried to explain, and borrowed insights of what constituted Indian geography from previous rulers which included the Mughals, the Delhi Sultanate, Chinese and Arab writers/travellers and even Rajput Rulers, many of whom were of foreign extraction themselves.

The ancient Agnikul Rajput, (the fire-born Rajputs), a group that was distinguished from the Solar and Lunar Rajputs, were said to have been the amalgamated descendants of the Hephthalite, Xionite, Hun, Kushan, Scythian and others, who had been gradually settling India from around the end of the 1st century BCE until around the 5th century CE. They were followed by another group of nomadic peoples famed for equestrian skills, the Turushka (Turks). They converted to Buddhism, long before contingencies started to convert to Hinduism or Islam. Colonial writers believed that segments of the Rajput, Jat and even the Gujjar were, in fact, the descendants of older nomadic communities.

It is one of the misconceptions of ethnonationalists extolling Hindutva Nationalism that Indian Muslims almost entirely converted to Islam from Hinduism, the majority constituting low-caste groupings escaping the persecution of the caste system. It is simply not true and aside from being contradictory when the same protagonists decry western misreadings of ancient Hindu texts such as the Manusmriti, they deploy caste-related slurs to stigmatise Muslims – low-caste converts to Islam.

Social status (prestige) and power go together, it is the rulers who have privilege, and not the ruled, who approximate to the cultural and social norms of the Rulers. In the case of India and the caste system, Muslims of Central Asian extraction ruled parts of India for a very long time, coalescing into the older nobility structures, and one can see how Rajput art, dress and courtly culture influenced the Mughal court. These documented norms expose the simplistic propaganda of ethnonationalists arguing that all Indian Muslims were foreigners and low-caste at the same time. Insecurities are behind a lot of the claims to delegitimise Muslims as an authentic embodiment of Indian history. Contrary to ethnonationalist claims, Islam is indigenous to India in much the same way Christianity is indigenous to Europe.

It was this history that I wanted to explore outside the strictures of politics, which is documented in the works of professional Historians and Archeologists, and others studying nomadism, which requires a well-defined ecology. The nomadism of Central Asia had been moving in the direction of the Iranian Plateau and then into contiguous regions of the subcontinent’s north westerly regions. As a population movement, it was less impactful on the sedentary populations of the Indian Plains, exponentially high on the Indo-Gangetic Plains. To give some perspective, around the 11th century CE, the population of the Iranian Plateau was estimated to be around 5 million people, with another 5 million residing in Central Asia. Nomads of Turkic descent from Central Asia massively impacted the demography of Iran, but they were unable to impact India during the same period. India’s population was estimated to be around 100 milllion people, absorbing such intrusions with minimal impact on its gene pool, unlike Iran. On the other hand, the north westerly mountainous regions of the subcontinent had never been able to support enormous populations either.

The Abu Hanifa al-Zutah of history was not just a Persian speaking Muslim

The history of nomadism behind the emergence of lots of ancient identities in the subcontinent that include the Jat is being forcibly erased, reduced to a primordial identity linked to the Panjab and farming. The earliest Arab-Muslim accounts of the Jat located the progenitors of this population in the Sindh region. Writing in the 8th century, Arab writers described the Jats (al-Zutah) as “war-like”, explicitly mentioning that they were recruited into the Armies of various rulers. Jats were described as soldiers and bodyguards, others rose to the rank of administrators and military generals. This is exactly how lots of the “Turushka” (“al-Atrak” in Arabic) became soldiers and rulers in “Hindustan” (India). The Arab rulers diverging from the Sassanian Rulers attempted to make the Jat a sedentary population, and they did this punitively. Given the refractory nature of the Zutah and their enormous abilities to rebel, they were described negatively. Centuries later, the founder of the Mughal Empire, Mirza Zahir ul-Din, otherwise known as Babar, also had a chance encounter with the Jat, who on this occasion were accompanied by another refractory group called the Gujjar. They poured down onto Babar’s Army and effected enormous losses, but they were eventually defeated, and Babar’s Turkic narrative of the defeats have become the sole authoritative version of the events. The Jat and Gujjar accounts have been erased from history.

A lot of the unwarranted prejudice generated by the earlier Arabic writings against the Jat has, however, found its way into a lot of anti-Jat smears one still hears today. Ironically, citified social groups with no sense of their own origin in places like Pakistan’s Punjab region want to crack jokes at the expense of the “rural” (gaon) Jat, who, unlike their counterparts, do have a history dating back to Iran’s Sassanian Rulers. It is a far more credible story than the one Pakistan’s citified proponents are posturing through, currently, (Urdu is a component of this new identitty), demeaning village Pakistanis when it suits them, whilst appropriating the memories of the very natives they stigmatise, the Jat and related groups. More bizarrely, they do this through the imagery of other reimagined ethnic narratives.

The Legend of Maula Jatt (2022) – Official Theatrical Trailer

Releasing October 13, 2022 – Only in Cinemas Worldwide #TheLegendOfMaulaJatt #MaulaJatt2022 From times untold where legends are written in soil with blood, a hero is born. Maula Jatt, a fierce prizefighter with a tortured past seeks vengeance against his arch nemesis Noori Natt, the most feared warrior in the land of Punjab.

Interestingly, the Zutah had a presence in the Iranian Plateau and Iraq, and it is said that the celebrated founder of the Hanafi School of Islamic Law, Abu Hanifah originally belonged to this lineage/background. He was wrongly identified as a native Persian on account of how a myriad of overlapping identities were collapsed into a singular narrative of “al-Arab” (the Arabs) and al-Ajam (the Persians; the boundaries were later expanded). Speaking Persian, natively, did not render Abu Hanifah a Persian, perhaps in the same way Jalal ud-Din al-Rumi has been incorrectly collapsed into a universal “ethnic” Persian identity linked with Afghanistan. The “Afghanis” (a projection) who spoke Persian originated from different groups.

To expand on such tendencies, 600 years later, the great intellectual and reformer, Jamal ul-Din al-Afghani (d.1897) wasn’t born in Afghanistan, but in Iran to a Shia family (al-Asadabadi). The polyglot was a seminary educated Shia and a man of enormous intellectual talents. In Turkey, he would be identified as Jamal ul-Din al-Istanbuli (of Istanbul). Wherever he went, he was seen as a potential agitator on account of the threat he posed to the ruling regimes. How his assigned group identity was conveniently instrumentalised, negatively I point out, “an independent Shia reformer amongst Sunni Ulema (Jurists approximating to power) challenging Western colonial hegemony through European ideas”, produced the requisite dividends, and Afghani was silenced, not by the Imperial Russians, the French or the British, who were all spying on him, but the Sunni Ottomons. His remains were later returned to Afghanistan despite his ancestral home being in Iran, such are the ironies of the modern world.

Rumi wasn’t yours: Afghanistan furious as Iran, Turkey claim Sufi poet

Who can lay claim to Rumi, the Sufi mystic who is one of the world’s most beloved poets? A bid by Iran and Turkey to do so has exasperated Afghanistan, the country of his birth, eight centuries ago.

Ancient populations in our part of the world were closely connected to an ambiguous Frontier Region that had extended across the mountains to Kashmir, where natives spoke the Persian language in addition to other languages. Persian was never viewed as the language of a particular people or Empire, but high culture and a much celebrated literary canon heavily influenced by the indigenous Buddhism of the region that gave birth to Sufism, expressed in a Persian tongue. Rumi and other poets excelled in this art. Ancient identities were thus, multifaceted and overlapping, but are now being singularised because of the incessant demands of ethnonationalists (ethno-nationalists) to collapse the beauty of plurality into the banality of singular nation-state identities or ethnic groups, rewriting history akin to the political priorities of the early 20th century Fascists.

One can see huge parallels across the world were nativist narratives are deployed.

Fractures ensue and entire peoples are erased from history.

Of course, lots of ancient literary traditions were connected with the patronage of rulers and sectors of society associated with courtly culture and trade. India’s Ethnonationalists do not like the idea that Hindu and Buddhist Rulers could have been foreign converts to Hinduism and Buddhism. They are trying to overturn centuries of insights that point in that direction. Numerous Greek and Central Asian Turkic rulers converted to Buddhism, and their descendants did not simply disappear into thin air. They may have coalesced into the subcontinent’s gene pool to the point of becoming indigenised, but this does not mean that they never existed, or had a separate origin outside the subcontinent, which they did, but not in the way nativists problematise “foreigners”.

Colonial writers had similar anxieties when narrating India’s history, but they were keen to understand the actual history of the peoples they had vanquished in order to co-opt them. They resorted to the geographies of ancient Greek and Persian writers, based on Alexander’s incursions into the area and subsequent developments. These insights matter because they blow a hole into the ethnonationalist propaganda that forcibly incorporates Kashmir State into an Indian and Pakistani nationalist universe of meaning.

British India is the Precursor to the Modern Concept of India

The political unit we call India is the creation of British colonialism, and it came into existence courtesy of new technologies and communication systems that connected periphery regions with a centralised bureaucratic structure for the purpose of commerce and the extraction of natural resources. When one turns to the documented history of territorial polities overlapping the region called Hindustan, the successor term to the Arabic ‘al Hind wal Sindh’, the idea of India was a Muslim construct, but this doesn’t sit well with Hindu Nationalists, and strangely, Pakistani Nationalists either. Indian ethnonationalists prefer the term ‘Bharat’ linking India’s history to an ancient epic called the Mahabharata, but again, the overwhelming majority of Indians have no connections with the Indo-Aryan speaking Bharat tribe, whom, we are told by Indian historians, ruled Eastern Punjab having migrated there from the North West of the subcontinent.

The English trading mission of the 1600s that morphed into a military conquest of an expansive British India during the 1770s created Pakistan in 1947 for reasons that were not necessarily conducive to the interests of the newly-constituted Pakistanis. Note my earlier remark about the Great Game. Muslim Pakistan was essentially a gift to North Indian Muslims, breaking ranks with Indian freedom fighters, who were resolute that they would remain independent of any post-colonial machinations. They belonged to an entirely different tradition to the ethnonationalists claiming the earlier struggles. The Congress Party remained neutral during the Cold War.

In terms of the Muslim League, not one of the pioneers of this Movement spent a day in a colonial prison unlike the activists of the Congress Party fighting for an independent India based on socialist principles. Pakistan was Britain’s solution to remaining relevant in a post-colonial India, something Pakistan’s nationalists have difficulties accepting. The Pakistan Army is a remnant of that priority, which might explain why it remains a burden on a society that is being squashed under its boots. The Pakistan Army fulfilled its role during the Cold War when the Soviets were defeated in Afghanistan 10 years after its invasion.

When Pakistan imploded in 1971 after a history of brutal repression against East Pakistani Muslims, the “Panjab Army” – (this was how the soldiers were described by East Pakistanis at the time) – committed a genocide against ethnic Bengalis. The West looked away, Pakistan was too important for it to be dragged to the Hague and indicted for warcrimes.

At the time I was exploring this history, I wasn’t doing politics. I’ve always been comfortable with a global world that doesn’t have borders. I grew up in the UK and have been impacted by the norms and values of its society, and I recognise the way I think may not be to everyone’s liking especially autocrats. I’ve never been afraid or ashamed to say what I think because it causes discomfort to people, even if I’m forced to reappraise what I believe to be true. I understand how bias works and try to critically reappraise whatever I’ve learnt of history through accredited sources. I accept that I could be wrong on any number of propositions, because I’m not ideologically driven.

Moreover, I’ve never cared for the diatribes of ethnonationalists decrying European colonialism whilst exhibiting the same tendencies. To me these attitudes smack of incoherence.

So, what came back from the google search engine?

Mirpuris are not Kashmiris…. Mirpuris are not Kashmiris …

Dribble Drabble

Google returned characterisations that were false, misleading, at times racist and prejudicial, and ahistorical. The whole thing seemed staged and politically contrived to effect a certain take-home message. The content seemed to cause a ripple effect across social media because of the power of print media, triggering nonsensical debates about whether Mirpuris were Kashmiris. The ethnonationalists, who were embroiled in the discussions would typically accede to the point that Mirpuris were not Kashmiris. The clue is in the word ethnonationalism, the idea that nation states must be connected with languages and ethnic groups – imagined memories according to Benedict Anderson.

Curiously, borne of enormous diversity themselves courtesy of mutually unintelligible dialects separated by thousands of miles of land, they were hypocritically instrumentalising singularity for Kashmir, all the while celebrating diversity for India and Pakistan, disingenuously. Ironically, they were doing this in the Hindi-Urdu language empowered by the colonialists they abhorred. It was colonial administrators who codified the grammar of Hindi-Urdu, up until that point an unassuming low-status variety, to communicate with the Indians they ruled and not the ethnonationalists surfing on the same colonial tide centuries later.

On the other hand, when entering into Treaty Arrangements with India’s Nawabs and Maharajahs – the noble class, the administrators would use Persian. Classical Arabic is the sacred language of Islam, whilst Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, and yet both languages seem divorced from the fascist-type ideologies that wanted to celebrate both country’s primordial past. Hindi-Urdu was a non-standardised dialect empowered by the British to appreciate the ironies of people essentialising ethnic identities they don’t understand. It was colonial administrators who codified and standardised Hindustani (note again, a low-prestige dialect), and then deployed it in the lower echelons of the British Indian State, creating false linguistic identities when they used different scripts associated with religion; “divide et impera”!

Even in India and Pakistan today, English has a higher status than Hindi-Urdu.

The same intolerant reductionists frequently don the hat of equality campaigners, and complain about colonial supremacists and their racialist claim that “P**** can’t be British”. It doesn’t seem at all bizarre to them that when they repeat the claim that “….Mirpuris can’t be Kashmiris…” because, apparently, “…they are Punjabis…”, on the strength of a debunked psuedo race science, they are calling into question India and Pakistan’s internal coherence. They have no sense of how ignorant they actually present outside the bubbles repeating their propaganda on Social Media.

It would be justified to ask why Indians and Pakistanis should have the right to self-affirm as Britons, Canadians, Americans, Australians, Germans, French – outside India and Pakistan – whilst the same fait accompli is denied to ethnic groups rejecting Indian-Pakistani occupational labels for their ethno-national homelands? Ethnonationalistic reasoning, if turned upside down, would pose serious problems for the credibility of countries characterised by diversity.

The 19th century idea that languages and ethnicities forge nations has no backers anymore in the place of its birth – modern Europe. In fact, it had no corresponding social history up until the point it was instrumentalised by colonial powers dividing the colonies they created. It was colonial administrators who created ethnic groups when they standardised dialects associated with provinces, arguing that the languages in question constituted seperate peoples. Today, how dialects were adjudged to share the same origin myth per the old colonial priority, would call into question whether the dialect spoken in Azad Kashmir is the same language as the one spoken on the Panjab Plains, which it clearly isn’t. There is no linguistic consensus that the native language of Azad Kashmir and the Punjabi of Eastern Punjab are the same language in the books of professionally trained linguists researching Indo-Aryan languages purely for linguistic purposes. The Indo-Aryan area is one enormous Dialect Continuum; dialects, by definition, merge into other dialects, similarilities between dialects do not automatically bind people within the same identities. It is the politics of occupation that makes such claims appealing in the first place, masking minority repression and the suppression of human rights.

This would be akin to saying, hypothetically, Spanish and Portuguese are related, so therefore Portugal must be collapsed into Spain, and it has no right to have a separate history to Spain because Spain occupies Portugal. The Portuguese language is then quickly demoted to that of dialect status – “it’s really Spanish”, to stop it from being associated with resistence politics. Spanish is adjudged the mother-language, and this observation is then repeated endlessly in print media and social media to the point where the false narrative is repeated by the Portuguese speakers themselves – all of whom have zero intellectual investiture in the ideas being espoused in their name.

To give further context to the Spanish/Portuguese linguistic analogy above, I merely need contrast it with Hindi-Urdu to capture a profound irony on the part of those who want to essentialise Kashmiris, ethnically speaking, all the while they speak the same language, insisting they are seperate people. The spoken Pahari of Mirpur and beyond is not mutually intelligible to the Majhi speakers of Eastern Punjabi, both are native speakers of two different languages, who when lacking exposure to diglossia would have difficulties communicating with the other. Contrast this with Hindi-Urdu; the Hindi of Indians and the Urdu of Pakistanis are mutually intelligible varieties of the same language – the two communities can communicate with ease. They have separate scripts and higher lexicons because of division and separation engineered by political projects of the late 1800s, early 1900s, creating two distinct ethnic identities – Urdu for Indian Muslims and Hindi for Indian Hindus. In other words, both communities want to actively distinguish themselves from the other. The farcical nature of the hypocrisy on display does not however embarrass the protagonists lecturing Pro-independence Kashmiris about ethnicity, because they have no concept of intellectual integrity.

This is dirty politics at play in its raw nakedness, but for Azad Kashmiris it doesn’t stop there. The ethnonationalists would then become migration experts, conjuring up fictitious histories about how Azad Kashmiris ended up in the Western Himalaya from Punjab. Selectively quoting irredentist type claims about castes/clans and their supposed homelands, they would try to rubbish Azad Kashmir’s connection with Jammu & Kashmir. They would argue that Mirpur had never been part of Jammu, let alone Kashmir, and that Mirpur was the homeland of the Jat, which means Mirpuris are Panjabis because the Jat are Panjabis. It was just assumed that if a people shared a caste/clan background, it implied that they descended from the same region and ancestors, revealingly, “always from India, and not Kashmir”, an idea that is so crass that it proved to me that the propagandists lacked a basic literacy even in the most basic of ideas.

Downward Mobility Vs Upward Mobility

Fictive genealogies, (the clue is in the word fictive), are fictions. These fictions are not simply passed down from generation to generation, they are adopted, and oftentimes, invented and reinvented by upwardly-mobile people, who would like to write themselves into celebrated historical events. Some people do this to escape prejudice and stigma (African slaves related to African Kings), others do this to get ahead in life, see Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Ubervilles and the Dubeyfields; the former having misappropriated the identity of the latter, ironically. It has become the staple of British culture to laugh at the more simplistic antics of ‘social climbers’ when they become upwardly mobile, and one can see this in the comedic portrayal of Mrs Hyacinth Bucket, (Mrs Bouquet). These attitudes go beyond code-switching, which is not necessarily linked to social status, but different linguistic environments.

It is much easier for non-landed groups to morph into new identities because they are mobile, approximating to the dominant groups they hope to coalesce into thanks to social adaptability. Moving into new areas – usually urban ones, is the story of the modern world. Rural people have become prosperous in the process of urbanisation, a phenomenon linked with globalisation and economic growth.

Ambitious people of formally humble origin try to reinvent their pasts to overcome the stigma of once being poor and downtrodden, which is a good indication of what is being prioritised. It is far more difficult for landed groups with substantial roots in an area to simply uproot; conflict being one notable exception. For instance, tribal settlements are named after ancestors, which is an indication of who the old ruling nobility were, and this continues to hold true for entire swathes of Pakistan, even as the ethnonationalists want to change the names of the old non-Muslim settlements. Dominant groups connected with their ancestors and settlements never voluntarily give up the memory of their past except during times of conflict and social tensions. This is what happened to the House of Windsor, the supposedly English Royal Family, of German descent, from the branch Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Queen Victoria, for instance, was a native German speaker. Her inner court spoke German natively. The Mountbatten surname was anglicised from Battenberg because of widespread anti-German feelings during World War I.

It is one of the more curious facts of history that the English royal family since the time of Duke William the Conquerer, of Norman-French speaking Danish-Viking descent, have never been English, ancestrally, per race claims, if indeed, there is such a thing as an English native, satirised by the poet, Daniel Defoe in his poem, the ‘True-Born Englishman’.

England

Etymologically, England is named after the Angles, who came from outside the British Isles, centuries earlier. The Angles, we are told, alongside a loose confederation of Germanic tribes that included Jutes, Saxons and Frisians, invaded and settled a Celtic speaking land during the 5th century CE that had been conquered centuries earlier by Latin speaking Romans. The Angles eventually became embroiled in a war with Scandinavian Vikings, and lost. If population geneticists are correct, the ancient Britons who built Stonehenge, 2950 BCE, lacked the genome that characterised subsequent populations with roots in the Central Asian Steppe (Indo-Europeans), being more closely related to Anatolian Neolithic Farmers. Contemporary Britons and Europeans in general descend from European Hunter Gatherers, Anatolian Neolithic Farmers and Central Asian Steppe Nomads.

Cheddar Man: Mesolithic Britain’s blue-eyed boy

Research into ancient DNA extracted from the skeleton has helped scientists to build a portrait of Cheddar Man and his life in Mesolithic Britain. The biggest surprise, perhaps, is that some of the earliest modern human inhabitants of Britain may not have looked the way you might expect.

Understanding the contradictions borne of primordialist-type thinking would give perspective to the delusions of ethnonationalists, who think in primordial terms, shouting “God save the Queen”, and then arguing there’s no “Black in the Union Jack!”

Saint George’s Flag, or the Flag of England dates back to the 17th century and was adopted by English seamen in international waters. St George, the Patron Saint of England was born in what is today Turkey in the 3rd century CE, having had links with the Roman Province of Palaestina. He had never set foot in England, which during his lifetime did not exist as an idea; his emblem – a red cross on a white background – was adopted by English Kings during the 13th century CE, subsequent to hagiographical writings that presented him as a virtuous martyr for Christianity. He thus became the Patron State for various Christian Kingdoms.

Downward mobility has been the norm for landed groups with claims of ancestral pedigree, whilst upward mobility has been the norm for individuals moving into new spaces, inventing their past by adopting honorific titles. This is absolutely the case in Pakistan where honorific titles of vanquished groups have become family surnames.

Pakistan’s Mrs Bouquet

Best of Hyacinth Bucket’s Name Mispronunciation | Keeping Up Appearances

There’s nothing Mrs Bucket hates more than someone mispronouncing her name, take a look at some of the many times she’s had to correct everyone. Subscribe for more exclusive clips, trailers and more. https://www.youtube.com/c/BritBox Get instant access to BritBox here: https://t.co/twQVv5eOG5 Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/BritBox_US Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BritBoxUS/ Watch unmissable BBC and ITV shows, any time.

In the case of citified Pakistanis – (upwardly mobile Pakistanis), one frequently encounters people claiming a foreign-origin to celebrated Muslim Rulers, who a generation or two ago, migrated from rural areas into market towns that became cities, receiving patronage from the Central Government. On the eve of Pakistan’s creation in 1947, seven percent of the country was urban to give perspective to Pakistan’s history as a less developed frontier region to North India, and this holds true for the expansive megacity we know of as Lahore, that contained the smaller Mughal city of Lahore.

Mughal Lahore was important because it was the route to Delhi from Central Asia via the Khyber mountain pass and rivers that meandered their course into the Plains of North India. Mughal Rulers seemed to have a lot of affection for the ruling tribes of the native rulers they incorporated within their extended networks, located within strategically important areas. They seemed to have less affection for the peoples they occupied, and this would hold true for the millions of inhabitants of Lahore today, who think they descend from Babur, or Tamerlane, and not the ordinary mass of society.

Of course, it is a well-known fact that Pakistan’s wealth is centred on particular cities where it is unequally distributed amongst sinecures of a corrupt establishment, which gives impetus for peripheral regions to break away, which is what is happening with Azad Kashmir. Unlike the anecdotes of upwardly mobile people, the history of Pakistan’s unequal distribution of incomes and wealth is documented by economists and sociologists writing about a neopatrimonial culture that values the idea of being urban (citified pretensions) in direct contradistinction to being rural, as proof of contrasting social status.

It is a priority that has not evolved out of the actual history linked with Mughal Rulers and their Zamindar clients, but the unequal distribution of wealth. Some rural elders of the Zamindar, responding to the primordialist charge that they were low-caste Hindus in previous centuries, encountering the newly constituted ‘Ashraf groups’ (Muslims of purported foreign origin) remind their grandchildren about the enormous transformation of “the low castes” – to borrow a pejorative insight of colonialists, “who only yesterday were landless Market-Gardners but today claim to be the scions of the great Mughals”. Colonial accounts of upward mobility corresponding to the adoption of higher caste identities by the formally, lower castes, are ubiquitous in colonial writings, see Sir Walter Lawrence’s, Vale of Kashmir (1895).

These conversations are rarely referenced by social commentators looking into Pakistan’s enormously plastic caste-system, because lots of the “native informants” belong to the upwardly-mobile groups, self-affirming through the false narratives they create for British Media platforms. They give themselves away when they point out differences between rural Azad Kashmiris (Mirpur is Azad Kashmir’s most urban area) and citified Pakistanis in the UK courtesy of how they’ve acquired such facts in the first place. The level of unconscious bias is clear for all to see when the corresponding descriptions are examined. It is bigotry and social differentiation that is at the heart of the discourse, and not sociological findings that mask the bigotry.

Ancestry

The idea of ancestry is, however, a fiction. Given how we inherit most of our DNA from our most recent ancestors – 50 percent from mum and 50 percent from dad; 25 percent from each of one’s four grandparents. It is highly unlikely that anyone has DNA from ancient ancestors, who lived 1000 or 2000 years ago, that’s approximately 40 to 80 generations ago. DNA is not passed on like that, but this does not matter for the self-styled descendants of an array of celebrated personalities in Pakistan now. There is an upwardly mobile component to these identities, which should explain the priorities behind the actual posturing. The Indian caste system has similarly been highly malleable. It is not a fossilised artefact of the past, but the invention of people who end up stratifying their societies through false narratives.

It was at this point that I realised something was terribly wrong in terms of how Mirpuris were being described counter-intuitively. I knew from my own research and background that Mirpuris belonged to dispossessed landed-groups, which, purportedly, had links to ancestral lineages, but had been increasingly marginalised over centuries of invasions and native co-option. It had been noted by census compilers of the 1901 Kashmir State census that families “of gentle birth”, to quote the exact words, had been forced to till their land, a demotion in status with symbolic meaning. To reverse a loss in status some left the State to augment their incomes – the ritual of building mansions on the proceeds of remittences is an attempt to restore an older past, which gets conflated with skewed narratives that feed off ‘the rags to riches’ storyline. Others became soldiers of the British Indian Army, accruing salaries that did not necessarily reverse decades of downward mobility. Working abroad and the stories told that, no doubt, romanticised the adventures abroad became an impetus for Azad Kashmir’s forebears to leave Kashmir State.

The Census Compilers (Munshis) noted that of all the Districts of Kashmir State, Mirpur Tehsil, then a subdistrict of Bhimbar District, had the least number of men residing in the entire State, either, on account of working abroad, or being engaged in military duties outside the State. Such was the impact of this lucrative pool of income that it otherwise counteracted the poverty within the District, improving the condition of those “of gentle birth”, whilst redeeming their social status.

Of the non-landed occupational castes who had left the state in droves during famines, the Caste Kashmiri community of the Punjab, (Kashmiri by Zat) comprised a large segment of a ‘refugee population’ that ended up in British India. Colonial administrators would describe Kashmiri colonies in the Punjab with disparaging language. Today, one encounters Punjabi Caste Kashmiris aggregating an “ethnic” Valley Kashmiri identity for themselves per a history they greatly misunderstand, only to have their identities instrumentalised by Pakistan’s ethnonationalists to cause confusion about the bonafide Azad Kashmiris advocating independence. It was observed by colonial writers that had the taxation on the sale of lands not been excessive – half the value of the entire estate, the landed groups would have fled Kashmir State, notably from Chibhal – the area with the most outbound migrants. As I said earlier, the Dogra Rulers of the State hadn’t initiated the cruel and exploitative practises they inherited in 1846. They were capitalising on the taxation policies of previous rulers. The tax collectors, Muslim or otherwise, from the Namardar communities (the disgraced Lord Nazir of Rotherham descended from this community), and those associated with the State through an official relationship of ensuring compliance with the State’s exploitative practises were similarly distrusted across the State.