The Evolution of AJK Public Agency

[THE FORMULA]

Citizen’s Opinion + Citizen’s Resources

=

Citizen’s Control of Public Policy

The most important aspect of modern-day governance is a consensus on public narrative, which is derived from an orderly aggregate of genuine public opinion. As the citizens of Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK) are the owners and inheritors of the public space in which they reside, it is exclusively their responsibility to ensure that the dominant public narrative is in conformity with public interest.

AJK’s geographic location coupled with its abundant precious resources (increasingly sought after by the regional as well as global economy) has proven to be a hindrance over 70 years of external administration/control/occupation. These characteristics can be converted to clear advantage for the local citizen if the state they identify with, first wins the war of narratives by exercising unhindered freedom of expression.

What was pre-1947 essentially a British sphere of influence south of China and (Soviet) Russia was arguably cut up according to British taste in 1947. Consequently, repercussions for democratic evolution here have been horrific. Entertaining the possibility of easing Pakistan and then India out of Jammu & Kashmir (J & K) – subject to ascertaining public opinion of each administrative region – is as much a responsibility of Britain as it is of local civil society (or public agency to coin a more contextual term) in AJK.

In general, our population (in AJK) can be described as a swamp of people wallowing deep in self-pity combined with invariably opting for self-interest at the cost of public interest. Indeed, of opting to escape from this territory rather than confronting the absence of governance. It is in this background that a thirteen years and three months journey of discovery has taken this writer from:

[Note; the comments section of this post has been deactivated because of the nefarious attempts of the hidden digital Occupier (everyone knows who they are), disappearing and undermining the indigenous voice of the Azad Kashmir Independence Movement. Such posts are also being removed from online search engines through algorithm manipulation. Pro-Kashmir posts have been infiltrated on this website. Portmir Foundation, (the Portal for Jammu & Kashmir Independence)]

(British) Citizen

(to)

A State Subject of J & K via AJK

(to)

Self-recognition in status as a disenfranchised local citizen

Before arriving here, I can confidently assert that I was neither a patriot, nor a nationalist or even a democrat. I was a journalist working in various conflict hotspots around the globe (Iraq and Afghanistan), had regular access to the corridors of power in Westminster and Whitehall while visualising a clear path to fame and fortune, despite it being laced with danger and dispute. As a Muslim exploring my faith as much as examining the concerns of a minority Muslim community in Britain; grappling with the spectre of terrorism, I was extremely sceptical about democracy and having any deep affiliation with any piece of land, East or West.

Before arriving here, I can confidently assert that I was neither a patriot, nor a nationalist or even a democrat. I was a journalist working in various conflict hotspots around the globe (Iraq and Afghanistan), had regular access to the corridors of power in Westminster and Whitehall while visualising a clear path to fame and fortune, despite it being laced with danger and dispute. As a Muslim exploring my faith as much as examining the concerns of a minority Muslim community in Britain; grappling with the spectre of terrorism, I was extremely sceptical about democracy and having any deep affiliation with any piece of land, East or West.

I could be described as all three now though I operate strictly as a democrat fuelled by patriotism but am heavily restricted structurally by a mixture of Indian and Pakistani nationalism.

It was felt that this journey to self-recognition should be reflected in my actions through un-interrupted presence here and utilisation of local resources; in the shape of the natural environment as well as human capital in the shape of my co-citizens residing here or in the diaspora. Thus, social/institutional experimentation took the following route over time:

Forum (namely Civil Society Forum – AJK)

(to)

Institution (namely Kashmir-One Secretariat)

(to)

Agency (namely AJK Public Agency)

Although a personal quest of family re-union across the Line of Control (LOC) brought me to the region in April 2005, my intentions soon took a public interest dimension upon realising that division of my motherland wasn’t just physical; it was emotional, calculated and essentially political in nature. A contest of ‘Ownership’ between China, India, Pakistan and the inheritors of the erstwhile Dogra State of J & K i.e. the aspiring citizens of the divided state.

After 4 years and 2 months, I was finally able to re-unite my naani (maternal grand-mother) with her siblings across the LOC. A surviving brother and 2 sisters met for the first and last time in 62 years. I felt that I had achieved my life-long ambition and was now ready to return to the UK to pick up my journalism career from where I had left it in 2005. However, the night before booking my return journey I couldn’t sleep. My conscience kept on reminding me that I had stubbornly spent 4 years in a territory to fulfill a personal ambition.

That wasn’t fair.

The research and activism that I had generated shouldn’t be confined to that single experience of catharsis. I had to struggle on for the sake of humanity in this region. Nothing in the world was more worthwhile, appealing or enriching. I had to do whatever I could to try and make a difference for everybody. Indeed, everybody’s naani deserved deliverance from this inhumane system of governance.

This evolution of thought and practice in AJK initially led me to develop the concept of Civil Society Forum – AJK in 2009, which held over 40 public forums from Bhimber in the south (of AJK) to Hunza in the north (of Gilgit Baltistan), involving a diverse range of citizens and covering all relevant topics that the public deemed important.

From arriving in 2005, I had utilised whatever I had in terms of personal resources and when they were exhausted after a few years, I relied on my family – which is of course settled in the UK – to sustain my journey.

This was followed by an attempt to develop an institutional structure through public (co-citizen) support in the shape of Kashmir – One Secretariat. Through this medium, I began issuing an annual public document which provided a summary of activity throughout the year, from 2010 to 2014. The research work hitherto conducted had produced over 2,000 videos, over 2,000 audio files, a similar number of photos and over 200,000 words of text; covering a wide range of publicly significant topics from the region’s history to the current structure of governance.

The Birth of AJK Public Agency: Narratives, Agency, Identity, Ownership and Rights

Understanding that the destiny of the J & K, many in AJK would more commonly describe it as the “Kashmiri”, freedom struggle lay in the hands of the public, it followed that recording public opinion was a powerful and indispensible tool in public interest. Under the previous nomenclatures of ‘forum’ and ‘institution’, my experience suggested that there remained a lack of clarity in understanding my work – as far as the public at large were concerned – while the external agencies that monitor and attempt to control public activity in AJK, continued to imagine that their approach was an exclusive right bestowed on them.

Understanding that the destiny of the J & K, many in AJK would more commonly describe it as the “Kashmiri”, freedom struggle lay in the hands of the public, it followed that recording public opinion was a powerful and indispensible tool in public interest. Under the previous nomenclatures of ‘forum’ and ‘institution’, my experience suggested that there remained a lack of clarity in understanding my work – as far as the public at large were concerned – while the external agencies that monitor and attempt to control public activity in AJK, continued to imagine that their approach was an exclusive right bestowed on them.

As I reached the climax of my public opinion research work, in the shape of a 10 question survey (divided into 4 sections to encompass the basic pillars of a constitution) randomly put to 10,000 citizens of AJK, who were proportionately divided by population throughout the 32 tehsils (sub-divisions) of AJK, I had recognised the need to move the public narrative beyond the red lines laid by Pakistan’s agencies.

The purpose of this detailed collection of data in public interest was so that the public of AJK can take a decision on their constitutional future, given that the ballot box here – amongst other limitations – does not provide space for expression of political choice. Neither is a plebiscite or referendum forthcoming.

Reasoning

It fills the missing gap in society that political parties in the State of J & K have not been able to penetrate since the power change-over in October 1947. In other words, conducting politics in AJK is almost pointless or ineffective without internal agency. Politicians – conformist to the status quo as well as nationalist – have been unable to meaningfully represent public aspirations. The conformists would surrender public aspirations for personal gain while nationalists would fail to sustain their efforts, as they were suffocated or compromised at every step.

Of course, the whole subject deserves much wider public discourse, which has never seemed forthcoming in AJK.

The genuinely dominant public narrative has yet to be defined here. We still cannot derive consensus on how we should describe ourselves to the outside world. Are we Indian, Pakistani, Kashmiri, JKites, AJKites, Azad Kashmiri, Jamwaal, Pahaari, Mirpuri, Poonchi, Muzaffarabadi or could we even be Pir Panjaali or Chenaabi? How do we refine our thoughts and ensure that we are not an extension of any other entity’s identity, or indeed their problems or aspirations? Obtaining acceptance of that dominant public narrative in AJK, is essentially the first task of AJK Public Agency. In due course, it could even take shape constitutionally as the AJK Public Empowerment Order.

Andrew Whitehead, a senior editor at BBC World Service News, historian and expert on the ‘Kashmir conundrum’in many respects, indirectly (as I’ve never met him) put certain fragments of thought previously combusting in my mind for months into place, when he described the Kashmiri nationalist narrative (as opposed to the Indian or Pakistani nationalist narratives on Kashmir) as, “Kashmiris have been deprived of agency over their own political dispensation by two powerful and feuding neighbours.”

Reference: Panel 3 University of Westminster seminar entitled, “Kashmiris: Contested Present, Possible Futures”

In the 1950s, the historian Robert Wirsing described Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir as “calculated ambiguity”. Today, in 2018 nothing has changed. Essentially, as the protectors of Pakistan’s occupation in AJK are its clandestine agencies, their activities can only be countered and civil democratic space restored by creating a civil public agency that generates information in public interest and statistically gathers public opinion in pursuit of self-determination. That by utilising measured and accountable support: in time, effort and resources obtained from the very citizens whose collective problem it is.

Self-Determination and Agency

Indeed the terms ‘self-determination’ and ‘agency’ are synonymous in this context. In a practical sense, self-determination cannot be asserted as a right or politely advanced as a humble aspiration that we wait indefinitely for decades for the ‘International Community’ to oblige us with. That while, India and Pakistan continue to do all the ‘bidding’ or lack of it on our behalf – internally as well as externally. ‘Agency’ is essentially using our own initiative to peacefully create, choreograph and sustain a solution that the world will notice. Nobody likes to help those who fail to help themselves.

The words ‘public’ and ‘agency’ in respect to AJK when used and accepted by the public, already has and will continue to gradually reclaim that denied civil space and lead to a clear, indigenously created political process. Thus, this is not politics but rather creating an appropriate administrative structure to ensure our citizens do not fall back into the ‘political trap’ that has prevented genuine political representation thus far. This endeavour – will in turn assist in solving the constitutional dilemma that AJK has suffered from since 1947.

Having worked on the ground consistently since April 2005, it has become evidently clear that the battleground for rights (and the right of self-determination) is a direct contest between Pakistan’s occupying agencies and local inheritors who cannot mobilise the public in any meaningful collective activity, either as an individual, an ideology or political party.

Nomenclature

Each and every dilemma in any part of the world has its own unique history of events, circumstances and solution. In this age of advanced mass communication, nomenclature – or nouns and naming words used – is everything. The word ‘agency’ in the divided State of Jammu & Kashmir carries a burden of baggage. This involves intimidation, economic strangulation, murder and espionage by occupying forces.

The very same word ‘agency’ if propagated in the public domain, by associating it with a constitutional solution could give the citizens a sense of ‘ownership’ that their participation in public transformation – however modest – could make all the difference.

Furthermore, as inheritors of the Dogra State, collectively as citizens; it is our exclusive right to create a mechanism to solve the constitutional dilemma we find ourselves in. The prerogative, burden of responsibility is likewise solely ours and no-one else’s.

Ownership-Building Measures (OBMs)

This is what I wrote in April 2011 as part of an opinion article for ‘Rising Kashmir’ (an English daily in Srinagar which was founded and edited by the recently murdered Shujaat Bukhari), the gist of which was referenced by a notable British academic (Professor Richard Bonney) a month later, in a round-table meeting on Jammu & Kashmir at the House of Lords in the United Kingdom:

“The idea of progressing from CBMs (confidence-building measures) to OBMs (ownership-building measures) is to revert the problem-solving ambit back into the hands of the primary stakeholders viz. The 20 million or so people living across the breadth of the divided State.”

Our society’s general approach to public interest has lacked thought and initiative. Creative thinking is absent and discouraged. We do not understand well enough the need and manner of how to value those who work in public interest.

Answers to all the questions in society are actually there in the society itself. One just has to find them, assemble them into a narrative, which cannot be done without agency.

It should be remembered that the dilemma of public affairs in AJK is rooted in its ambiguous constitutional status. It is neither legally claimed by Pakistan nor positively pursued by India. The international community does not officially communicate with it without the consent of Pakistan, yet AJK describes itself as the ‘free’ part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, unrecognised on any global forum.

Not every citizen is interested in politics and neither is this ‘agency’ venture a political campaign. However, our common dilemma – irrespective of whether we are conscious of it or otherwise – can only be tackled in an administrative manner through creating genuine public agency in AJK.

Three requirements for laying the ground for Internal Political Process

1) Participation

– Which should be horizontal as opposed to vertical in the sense that every citizen – irrespective of their ideology or affiliation – has an equal opportunity to contribute towards. Vertical structures generating a ‘clan’, ‘party’ or a group of individuals hovering above the rest of the public would be anathema to such a conception of agency.

– Identify and utilise capacity of public to give time, resources and effort/intellect.

2) Awareness

– Of outstanding national question, collective inheritance of land in question and civil rights.

3) Managing conflict of interest

– Outside interference/manipulation of prevailing issues, preventing personal benefit from destroying collective interest and maintaining it till resolution.

Hence, AJK Public Agency is an internally created and funded route to ownership of public space in AJK. Whereby, every citizen of AJK is requested to kindly play their part in utilising their private resources as a collective public resource.

Public Agents

To identify ‘public agents’ who can work full-time primarily as researchers (involving data collection, administrative duties and activism) although a gradual need for database programmers will also emerge in due course. Their research would cover public opinion on all matters of public significance, developing a database of citizens locally as well as in the diaspora, measuring the economy of AJK, logging the status of human rights, developing a historical timeline of the region over the past 200 years, identifying and working for creative initiatives in art, craft, culture, heritage and sport.

There is of course no reason to be restricted to the aforementioned, subject to public approval. It should also be emphasised that all aspects of AJK Public Agency are of a voluntary nature and transparency, meritocracy and accountability to the public would be the pillars on which it could sustain its utility.

Criteria

1) Non-political (in terms of party affiliation and interest beyond desiring the state of AJK to be in control of its public affairs)

This does not mean that they are not entitled to a personal ideology or political preference. However, their duty and activity would operate just like any administration in a modern day democratic governing structure.

2) Business-free (beyond or except subsistence rent or duty)

This means that they should not be part of a business lobby, which at some point may derive benefit at the cost of public interest, through utilizing that public agent. Of course, many people hail from families that have business interests but that should not disqualify any citizen as long as they don’t use their position to further private business interests. It should also not disqualify citizens who run small scale businesses in their spare time.

3) State Agencies-free (To not be operating as an agent of any sovereign nation-state or similar entity beyond the borders figured at c. 85,000 sq. miles)

There would obviously be a conflict of interest if any citizen were to be working for any other country.

Funding

These public agents would be paid a salary directly from public funds generated from the public. Each of them would generate a daily activity log (based on a pre-determined schedule describing the range and scope of their research/admin/activism duties).

Salaries (output) and public funds (input) would have to be regulated so that the integrity of public interest could be protected. For example, there would be a maximum that any individual citizen could donate in a year and all donations would be as individuals; not from any party, organisation, group etc. Furthermore, all donations would be accepted from only citizens of AJK or its diaspora. That also means that citizens of Gilgit Baltistan, the Valley of Kashmir, Ladakh or Jammu would not be able to contribute at this point in time.

There should be a committee overseeing the operation of AJK Public Agency, which should be a representative sample of the population. However, there needs to be further discussion/consultation with the public on its structure and criteria.

Gradually, 5 layers of the administrative structure of AJK Public Agency would emerge:

Layer 1; Division

There are 3 administrative divisions in AJK namely Muzaffarabad, Poonch and Mirpur. Initially, 3 public agents corresponding to the 3 divisions should be identified and employed.

Layer 2; District

There are 10 districts in AJK, therefore a further 7 public agents should be identified and employed corresponding to each district of the territory.

Layer 3; Tehsil (Sub-division)

There are 32 tehsils in AJK, therefore a further 22 public agents should be identified and employed corresponding to each tehsil of the territory.

Layer 4; Union Council

There are currently 194 Union Councils in AJK, therefore a further 162 public agents should be identified and employed corresponding to each Union Council of the territory.

Layer 5; Moza (Village)

There are 1,771 villages in AJK, therefore a further 1,577 public agents should be identified and employed corresponding to each village of the territory.

By this stage, we will have an administrative structure of governance that could compete with the most advanced countries in the world. Indeed, we would have progressed beyond Switzerland which is currently considered to be the most advanced democracy in the world!

It should be re-iterated that there is much further discussion to be had with the public on this proposed structure. Although much thought and practice has gone into devising it but it can by no means be considered as concrete and final, without being interrogated by the public at large for its practical implications. However, as it is a sequential procedure there will always be opportunity to refine and re-assess the objectives and performance of the whole exercise.

Day to Day Activity and Monitoring by the Public

Until public activity doesn’t convert to such a format, it won’t gain momentum for institutionalising a movement to take it to its logical end.

A Summary of the Purpose of AJK Public Agency

To actively promote public interest – in and via AJK – through an indigenously created and funded institutional framework. This would lay the foundations, identify capacity and ultimately provide the appropriate tools for developing a consensus on governance and public policy in AJK.

AJK Public Agency is a culmination of a decade long pain-staking socio-political research process that eventually identified a gaping void in the practicalities of the Ownership-Building Mechanism (Measures) see OBM ref. 2011:of AJK in particular and the erstwhile Dogra State of J & K as a whole.

The people of J & K, whilst constantly straining for recognition as exclusive arbiters of their distinct abode and uncertain future – as subjects under autocracy cum citizens under democracy – have attempted to exercise their ‘right’ through various political party orientations, local/regional/global legal and diplomatic activism, education, social work, philanthropy to outright adventures of plane hijackings, kidnappings, guerrila warfare and a prolonged armed struggle (also described as a proxy war in another context). However, different challenges surfaced throughout the decades since October 1947; including perhaps most significantly, close monitoring and manipulation by external state agencies belonging to the neighbouring countries, forever vying for control of public opinion and consolidation of captured territory, at any cost.

Difference between a conventional nation-state agency and AJK Public Agency

Conventional Agency AJK Public Agency

| Clandestine / Opaque | Transparent / Accountable |

| Use of force / Torture/ Kidnapping | Voluntary / Consensual / Persuasion |

| Security Concerns – Protection | Data Collection for governance – Advocacy |

| Limiting – Disempowering | Expanding – Empowering |

| Surveillance – Monitoring | Research – Discussion |

| Dogmatic – Closed | Creative – Open |

Both types of agencies claim to be operating in ‘national interest’, are funded by the public (the former directly through taxes and the latter by voluntary public funding) and have the best interests of their ‘people’ at heart. It should also be pointed that we are not vilifying any particular country’s security structure but rather explaining the context of AJK in light of our experiences. Our intention is to resolve our collective dilemma that affects us all as co-citizens in a given territory, namely AJK.

The request to the British Government at some stage would be to officially recognise that an internal narrative exists in AJK, which may not be clear or refined as yet but there is clear evidence that it differs from both the Indian and Pakistani nationalist narratives. This could be achieved by lobbying the 650 elected MPs in the UK Parliament.

As for the AJK diaspora – in the UK in particular (for their sheer number as well as British colonial legacy) and the rest of the ‘developed’ world in general – we would suggest that access to:

-

Economic Opportunity

-

Protection of life, wealth and honour

-

Access to justice on an equal footing

Are all facilities that you enjoy which are precisely absent here in AJK. They didn’t emerge where you live without struggle and sacrifice. Likewise, we can’t achieve these objectives of governance here without contributing our fair share of effort, time and resources.

The terms pro-life and counter-terrorism strategy should become synonymous in our journey towards fulfillment of agency, autonomy and transformation in AJK.

Finally, I’ll end with an example of how public interest in AJK is regularly quashed for the sake of protecting Pakistan’s ‘national interest’:

In February this year, the Pakistani Foreign Office in Islamabad – through its clandestine agencies -intimated to the Deputy Commissioner (DC) of Kotli to warn of ‘harsh action’ if a persistent #WhiteFlag and #SignatureForPeace campaign in Nikyaal, conducted by victims of cross LOC firing (who were being killed or maimed regularly by Indian and Pakistani cross-fire) and other co-citizens were not abandoned.

“Pakistan’s reputation in the ‘international order’ is at stake”, was the reasoning given for this warning.

This means that we – the persistent victims – are not allowed to create agency for resolving the very tragedy imposed on us. This is akin to being prevented from mourning our dead. DC Kotli was of course only doing his duty as a pliable messenger.

Picture of author with Sardar Shamim Khan, the gentleman who threw his shoes at former Pakistani President Zardari in Birmingham, 2010 and who is widely esteemed on account of this individual act of protest. In the backdrop are clouds of Neza Spania, between the borders of Rawalakot and Abbaspur.

Picture of author with Sardar Shamim Khan, the gentleman who threw his shoes at former Pakistani President Zardari in Birmingham, 2010 and who is widely esteemed on account of this individual act of protest. In the backdrop are clouds of Neza Spania, between the borders of Rawalakot and Abbaspur.

“A person is a person through other persons. My humanity is inseparably bound up in your humanity. I can’t be all that I can be, until you are all that you can be.”

Desmond Tutu

Documenting Life In Azad Jammu Kashmir

Matiyaal Mehra near Rawalakot; pre-1947 chashma (spring) and the holes have been naturally carved out of the stone by the water.

Remembering a life-long public rights activist Sardar Aftab Khan of Thorar in Ali Sojal, Rawalakot.

Devi Gali near Hajeera in District Poonch.

Picture of author descending from one of the hillocks in Ali Sojal, Rawalakot

Picture of author descending from one of the hillocks in Ali Sojal, Rawalakot

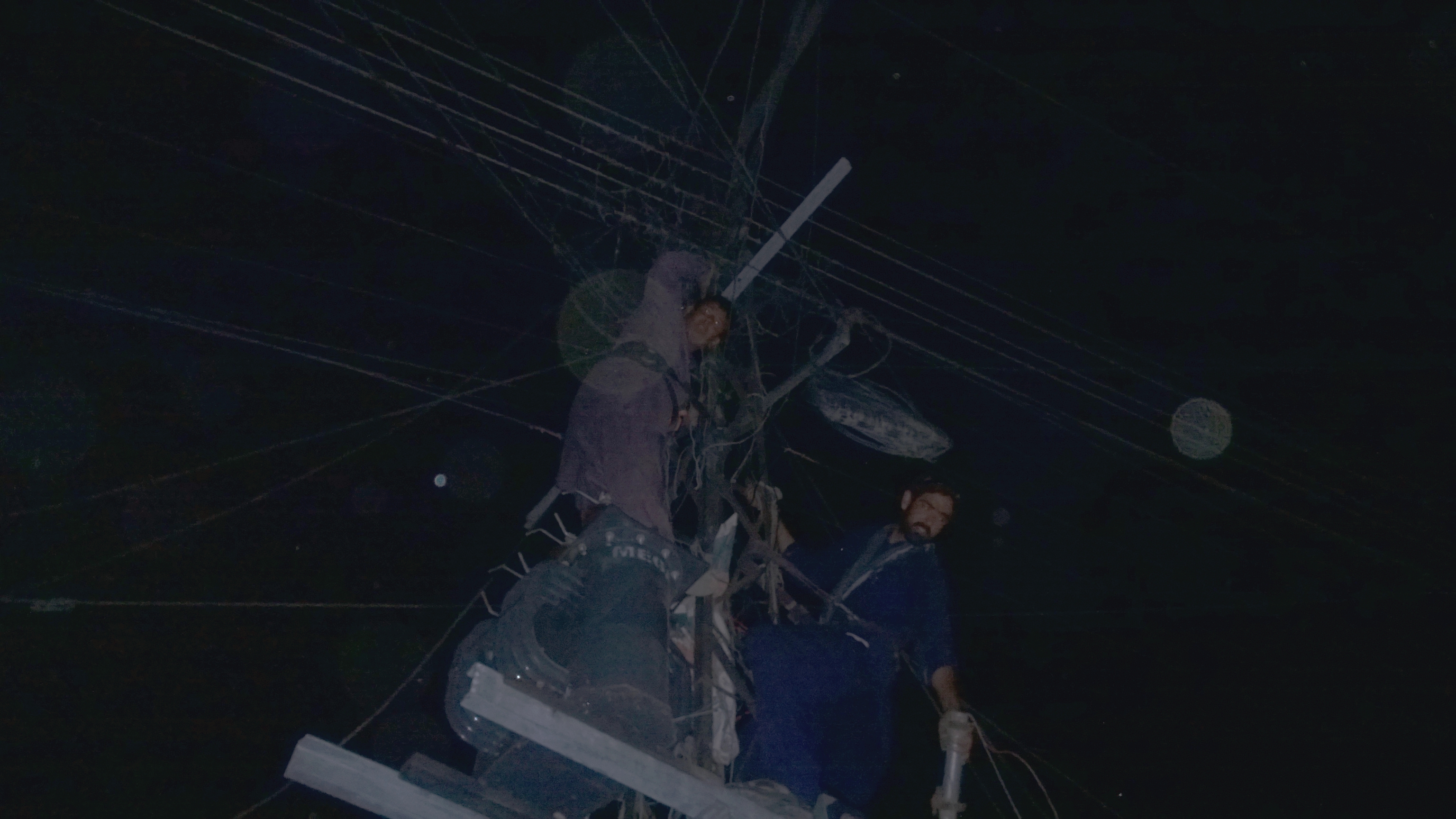

Two employees of the Department of Electricity in Dadyaal. Their work involves maintaining and fixing a cobweb of potentially life-threatening cables on a pole without having been provided safety equipment; an apt metaphor for the state of Azad Kashmir.

Life goes on, and re-emerges, as these children play on the very land where Sikhs used to congregate at the Gurdwara pre-1947 which can be seen behind the children. This is at Chappa ni Taar, Rawalakot.

Old and young alike in aspiring mode in a conflict zone amidst a white flag of peace, in the clouds at Neza Spania, between the borders of Rawalakot and Abbaspur.

This is Pura, a rounded abode, pre 1947, in stone; I couldn’t establish whether the gigantic stone structure jutting out of the mountain was carved by humans or by nature. It has the River Poonch surrounding it on 3 sides near Gulpur. There are remains of a building here and it has fantastic views of many hillocks around it. A tantalising view from atop. You can see a comprehensive video of it here, click here.

A tractor, normally used for farming purposes, is carrying waste in an open carrier where a lot of it falls onto the road and wayside, on its way to being dumped in some undisclosed site. Most refuse vehicles, in the developed world, transport waste in secure containers according to waste-management systems. Here it is just dumped, out of sight, out of mind.